Taiwan, 1971

Directed by King Hu

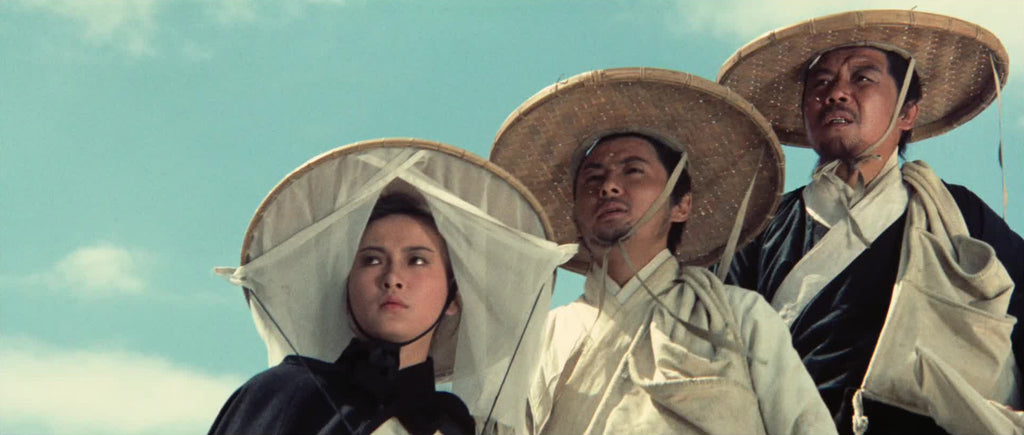

With Shih Chun (Gu Sheng-tsai), Hsu Feng (Yang Hui-zhen), Bai Ying (Shi Wen-qiao), Hsieh Han (Lu Meng), Roy Chiao (Abbot Hui-yan), Tien Peng (Ouyang Nian), Wang Rui (Mun-ta), Han Ying-chieh (the chief commander), Zhang Bing-yu (Sheng-tsai’s mother)

This is the evening: Gu Sheng-tsai comes to the huge, dilapidated house adjoining the house where he lives with his mother, at the time set by the mysterious, nice-looking but stern young woman who has chosen to live in there. He gingerly walks through the sprawling place, guided by the tune of a song. A wide, high-angle shot shoots him proceeding to the pavilion where Yang Hui-zhen plays music and sings. The camera gets closer as he sits down to hear and to gaze at the delicate creature in front of him. Then it pans to the right, beyond the woman, to shoot part of the lush garden; it moves back to focus on the man but briefly and it pans to the left, showing water lilies; finally, it focuses back on the space between the bewitched lad and the bewitching lass, and pans upwards to shoot the moon. A cut, and Yang Hui-zhen wakes up in the bright light of a new morning while Gu Sheng-tsai is still sleeping at her side.

The sequence is a wonderfully kinetic and genuinely poetic vision of love seizing two young persons, leading to physical pleasure, with a stunning ability to suggest the strength of the passion while skipping over words and gestures. This is a spiritual vision smoothly and smartly overflowing the frame carefully set by the plot, an aesthetics positioning itself into a wider, more contemplative set than what action requires. And this is simply the story of this film’s narration – and a symbol of its audacity.

At its core “Xia nu – A Touch of Zen” is a wu xia pian – and fights are many: the gist of the narrative is a bold series of complicated shenanigans and breathtaking swordplay that instantly stands a cut above what the genre was then churning out thanks to directors King Hu and Chang Cheh; both men have been working to inject fresh blood and new imagery in this kind of popular cinema and commercial and critical success has started to award their imagination and skills. A new release amid the growing flow of brand-new wu xia pian the film has a plot reminiscent of “Long men ke zhen – Dragon Gate Inn” shot in 1967 by King Hu – set a little earlier, the story again takes place at the fringe of the Chinese Empire, near the vast lands of Central Asia, still in a small place neighboring a half-destroyed fort; and it pits the ruthless agents of a central power dominated by ambitious and vicious eunuchs against the supporters of an opponent – in this case in fact his daughter, who is that fascinating Yang Hui-zhen, pretending to be a poor woman looking for a shelter and a rest, and two former generals, Shi Wen-qiao, who pretends to be a blind astrologer, and Lu Meng, who pretends to be a doctor. The narrative tells the increasingly amazing and bloody efforts of the opponents to escape the traps of the authorities’ representatives, first official Ouyang Nian, then his boss, Mun-ta (the official Yang Hui-zhen’s father tried to topple), and finally by the imperial army’s chief commander.

But the film does not start with a fight or a political scene or even the wandering of the unlucky heroine: it rather follows the mundane life of a calligrapher and painter eking out a living with his little talent. And that beginning soon becomes the relaxed chronicle of a funny daydreamer always quarreling with his assertive and obstinate mother. Gu Sheng-tsai yearns for a quiet life dedicated to knowledge and the brush and he is in no hurry to become a civil servant or a married man – the tiffs between the young man and his mother and his knack to make blunders turn the film into an enticing comedy of temperaments that is slowly upset by the mysterious atmosphere emanating from the house next door or the suspicious attitudes of a new client, a traveler who is actually Ouyang Nian starting to search for Yang Hui-zhen and her companions. The innocent calligrapher stands as an offbeat, off-center character set to guide the audience to the true, suspenseful, and spectacular, plot. The film partly sticks to his viewpoint and thus casts the fighting and the politicking into a more distant light emphasizing their violence and disregard for ordinary folks.

Still meeting Yang Hui-zhen is a chance for Gu Sheng-tsai, not only because of the romance but because he can use his knowledge to shape the struggle and help the opponents win over the power. He does not quite cut a daring figure and swordplay spooks him, he is more a scribe observing life carefully than a warrior shedding blood carelessly – this a wonderful, deadpan performance for actor Shih Chun, playing against the type he had in “Long men ke zhen – Dragon Gate Inn” – but he manages to craft tactics that deliver victory, though in an unorthodox, comical way: this is the amazing transformation of the fort into a haunted place where troops led by Mun-ta are one by one defeated as much by panic and fear as by the expert swordplay of Yang Hui-zhen, Shi Wen-qiao and Lu Meng (who alas gets killed). But the character of Gu Sheng-tsai would be pushed aside as the story veers into a new territory.

Gu Sheng-tsai is still the starting point of the narrative: he thought he could stay with Yang Hui-zhen but she avoids him and writes to him they cannot have an affair. The young man, now a more sober character rent by sorrow, wanders through the region – but he is wanted by the authorities now, and Yang Hui-zhen and Shi Wen-qiao are forced to help him. In fact they are ordered to do as much by Abbot Hui-yan, a Buddhist running a monastery in the vicinity who has previously helped the rebels and fought with Ouyang Nian.

Played with a towering confidence, astonishing magnetism, and riveting physical strength by Roy Chiao, he is more than another mysterious and thrilling character of a fantasy tale; embodying the alliance of powerful and magical fighting skills and intense religiosity, he brings a far more spiritual and fantastic dimension to the film and the genre. The ultimate fight between the commander in chief and the abbot, a two part story featuring graphic violence and amazing images, becomes an outstanding confrontation between a wicked temporal power and a compassionate spiritual power, between contentious political allegiance and noble spiritual aspiration, between wicked cunning and candid force.

Camerawork and special effects illustrate in a fluid and bold style the rising tension and the increasingly bitter fight, till death settles it – the director demonstrates a flair, an imagination, and a vision that are mind-blowing and brilliantly expressed. Well before the ending acrobatics and fantasy have already made some scenes unforgettable, splendid choreographies of fighting that exploit in surprising twists the space where they occur while widening the possibilities of the image – this is the famous case of the clash between three guards and Yang Hui-zhen and Shi Wen-qiao in a bamboo forest, the trees standing as a grid holding the fighters prisoners and curbing their moves before becoming an arena where the trunks are perches and the guards lose their poise and their lives; there are also those impressive nocturnal fights, as dark shrouds the adversaries and confusion makes jumping and lunging thrillingly dangerous and unreal.

But in this final part the crisp, striking quality of the image is shaken up and opens new horizons: the pristine positives morph into colored negatives and a realistic body must grapple with an aura-like image. It is as psychedelic and befuddling as images of the final, ethereal voyage of the lead character in “2001: A Space Odyssey” (1968). And it takes this notional wu xia pian into a fresh direction, which actually hint at the next movies of King Hu, focused on shaolin and supernatural fighters: the story goes well beyond archetypes, impressive stunts, and references to history and culture to reach a religious illumination; the images overrun the genre; from the ordinary life of a regular man to the rising into heaven of an abbot, they embrace the whole cycle of life beyond politics and violence. The plot typical of the genre is somehow scaled back to depict a wider vision of the world and to make entertainment a moment of contemplation.