India, 1970

Directed by Mani Kaul

With Gurdeep Singh (Sucha Singh), Garima (Balo), Richa Vyas (Balo’s sister)

The hand throws a stone to get the fruit, then it picks it up on the ground, and extends to give it to another hand which seems ready to take it, but hesitates, and then wrenches it. The face of the young girl who has just snatched so angrily the fruit appears, a sullen face ferociously biting into the fruit, only to spit part of the pulp and briskly turn away.

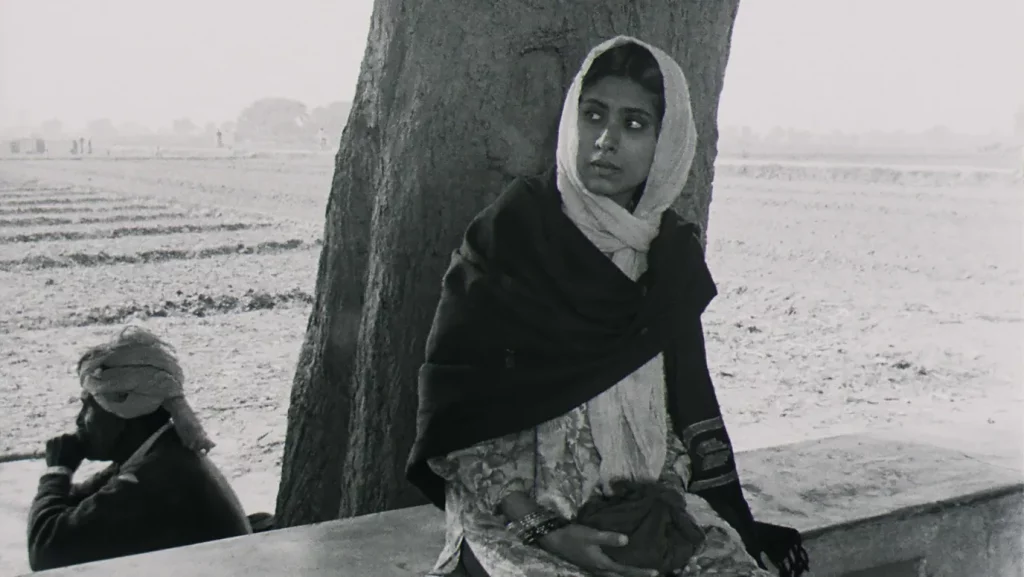

In the few shots opening in a quiet – no voices, no music, just the ruffling of the leaves – but abrupt – hard to describe exactly the effort of picking the fruit and the reaction to the gift – and definitely surprising way this melodrama, a lot is already showed. The story takes place in a countryside where crops can be good but the climate is harsh – the soft, slightly overexposed, light and the texture of the image suggest scorching sun and heat. Relations between people are fraught. And the film intends to take its time to observe, with closeups and in carefully arranged shot compositions, gestures, focusing on body parts rather than the full body of the character as expected. It is not going to be a frantic narration but would be deeply entrenched in the experience of time and sensation of folks from a distant corner of the vast Indian countryside.

The scene proves to be a bit misleading in retrospect: the relation between the two women is not as bad as that hesitant hand and that sullen young face hinted. They are sisters, living together and helping each other. But it is true that the sister of Balo, the elder of the two characters and the film’s female lead, can be cantankerous, challenging her sister and pointing out the problems in Balo’s marriage and in their wider life – the first dialogue between the sisters quickly revolves around the way an old relative clearly tries to seduce and to have sex with Balo’s sister.

The tension in Balo’s life lies in the distance between the young woman and her slightly older, far less nice and gentle husband, Sucha Singh, a bus driver shuffling between a big town and the surrounding villages. Once again, his is first a visual story of hands, gestures, face, appetite: he is shot in a kind of inn, devouring a meal, his hands grabbing the food and later paying the servant as dismissively as his remarks and glances at the skinny smiling fellow have been. Sucha Singh clearly belongs to the town, spending a lot of time with other patrons of the inn playing cards, sleeping in one of the inn’s rooms, decorated with pin-ups, or petting his mistress. Travelling back home is more part of the job than a real pleasure to get back to a household: he barely strays from his bus, barely speaks with Balo, barely cares for the bread she fetches to him every day. The wonder, raising questions that a conspicuous lack of backstory thwarts from providing answers, clues, information, is that he has ever married with this girl in this place (perhaps the village is his hometown, but the fact he is well known after all does not mean a lot).

The editing pits the couple’s house and the countryside, an environment both sparse and luminous, with the far darker, more crammed, more teeming shots of the inn: alternating pictures bears testimony to that gap between husband and wife. And gestures only emphasize the point: Balo is always shot getting busy with the menial, daily chores of cooking and cleaning, or walking to reach the bus stop where she would wait to her husband’s bus to show up to hand over that daily bread she carefully holds between her hands on her laps, while Sucha Singh is shot enjoying his card plays, his food, his bed, his mistress, and at one point carefully prancing in a mirror, getting his hair and beard as tidy as a good Sikh must, with an amazing and annoying smug air, but also moving up and down the inn’s treacherous stairs, that other tireless and repetitive movement, along the driving of the bus, defining his presence in the world.

But the editing is not always such a straightforward narration. As the running time extends, it starts to feature events that do not quite fit the linear narrative the audience could have been expected and tends to repeat specific views by adjoining different angles from where the image has been taken. A slight sense of confusion arises, suggesting uncertainty and highlighting existential malaise and problems. How does Sucha Singh really view himself and his married life? Is he that satisfied with his specious double allegiance to the countryside’s marriage and the town’s life? Some shots in his inn’s room hint at boredom but the scene where he tussles with the relative harassing Balo’s sister implies he is eager to protect his family and assert his authority, but then when exactly the beating took place is not quite clear and it may just express his deep-seated taste for violence. And what does Balo want, what is the purpose of leaving one late afternoon her sister and home, starting a strange, painful journey through the night that brings in an eerie and poignant manner the film to its ending? Is it just about bringing this daily bread which looks like a foolish obsession, or does she reckon something else?

Her abrupt departure follows an event that horrifies the village: a woman, who has been long neglected, and cheated on, by her husband, has thrown herself into a canal to death. So Balo was not an isolated case but, to the dismay of her younger sister, pretended not to be aware of her hubby’s flaws. That other unhappy wife refused to keep condoning the misbehavior of her own husband: her tragedy, which is a loud and clear and terrible statement, is shot extensively, the effort of retrieving her body as shocked folks gather being the center of a long, superbly composed, sequence. Is it going to be a turning point, prodding Balo into confronting her husband?

That could have explained the night walk. But the way it ends, treated in a staggered narration, proves to be a bitter, absurd disappointment: she does meet Sucha Singh, who this time turns out to be meeker that has been so far the case, gentler too, quieter on the whole, and Balo once again accepts he slams the bus’ door on her to keep riding through the land. Back home, she finds out her sister has been assaulted: she failed this time to evade the grip of the male predator, though there is no certainty the culprit is the previously shot lustful relative. Women remain stuck in a thankless, humbling social position, unable to escape a male domination that is violent, selfish, relentless.

It is not with hands but with a face that the film concludes, a long take in a dark background on Balos’ quiet and sad face: her agony is plain but she is also keen to abide, aware of what her husband really is and yet clinging to her marriage, out of habit and tradition probably. Her gaze is directed at us as it has never been so clearly and intensely in a film where shooting profiles has been a prevailing rule: the audience is forced now to consider carefully what has been her narrative arc and to respond to the dead end where Balo and countless women stand helpless.

It is not just the story, the interrogation, the odd, highly aesthetic and sophisticated shots that stun: the relation to time, including the remarkably slow pace of the narration, the emphasis on silence as well as on ordinary, natural sounds, be it the rushing wind or bottles being put on a counter, or a cat mewing, or a bus riding, the slim characterization and contextualization make “Uski roti – His Daily Bread” a most demanding and fascinating film, shaping out of the cinematic grammar and vocabulary a space, a soundscape, a full world that conveys what the characters experience as life goes on, or rather stumbles forward, in the tedious environment of a distant countryside where social inequity and narrow-minded mentality run. This is definitely not Bollywood staple, and this is not quite what the Indian arthouse cinema, embodied by one Satyajit Ray, to drop a too well known name, is up to: this feature by Mani Kaul looks like a groundbreaking and radical event – and of course, it elicited in 1970 far more anger and disbelief than support and interest. But incredible it was – and incredible it still wonderfully feels.