France, 1985

Directed by Agnès Varda

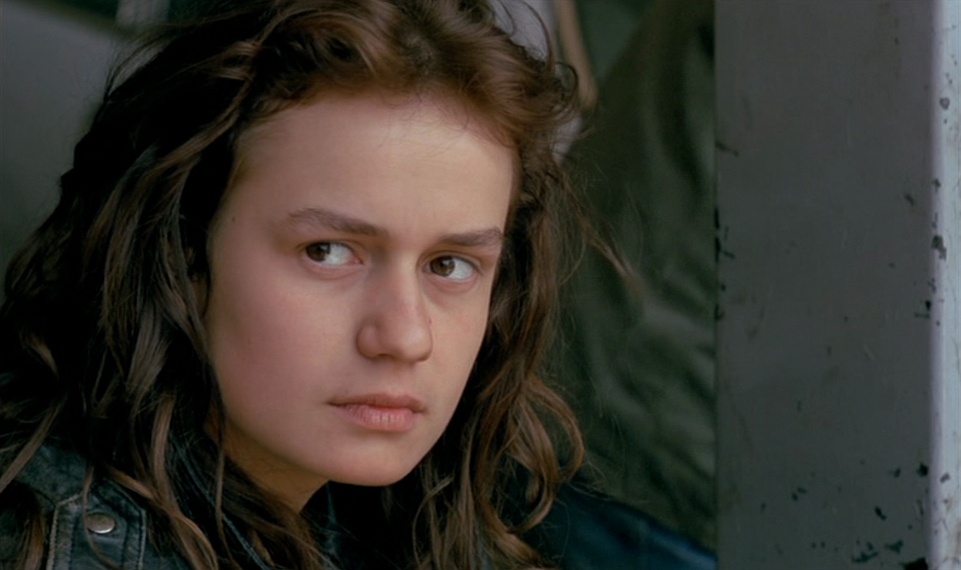

With Sandrine Bonnaire (Mona, born Simone Bergeron)

A farm worker finds in a ditch the frozen corpse of a young woman seemingly in her 20s early in the morning of a winter day in the French department of Gard, which lies along the Mediterranean sea. Members of the local gendarmerie briefly examine the place and interrogate a few persons before carrying away the body. She was a vagabond who had no identification papers and nobody comes forward to claim her body, so she is buried anonymously in the local cemetery. But now that the work of the authorities is over art can take up the story of this victim of cold weather and destitution: the filmmaker talks over images of sand, telling her audience she is now going to investigate what happened to this anonymous woman and who she actually was.

This clear-cut, brutal opening sequence is followed by a two series of pictures the editing delicately intertwines. On the one hand there are vignettes focused on people who had crossed paths with the vagrant; they are supposed to describe what this motley group of people witnessed and eventually to publicize their opinion. Depending on the persons and circumstances, the shooting will take many forms. Some talk directly to the team behind the camera; others talk with the camera seemingly hidden and waiting to catch their decisive words; finally, there are a few cases when the persons are genuine characters carrying on with their own lives (and even involved in distinct plots) and who happened to meet the vagabond and the film takes time to follow their narrative arc, without losing sight of the deceased girl’s own narrative.

On the other hand there are scenes of various lengths depicting the events she experienced during the last weeks of her life. Either walking through the frame or standing at the center she always takes the center stage. Staying alone or interacting with others, she cuts a deeply daunting figure. Her face unremittingly looks sulky, stubborn, and sad – an ephemeral, shy smile appears only when she feels she can truly relax or must be polite, for instance with a driver who took her on the side of the road and is more generous and tolerant than need be, or a lover she genuinely likes, usually a man of her age and as much of a drifter as her.

The camera is keen on capturing her vivid, decisive gestures, even when dishonest and shocking. Her body looks like a force forging ahead no matter what, even if it means losing balance and decency, the absolute freedom of movement she has been looking for driving her and justifying her. Yet there is always the feeling that this force is going to waste: the camera follows her walking through the frame up to a point when it focuses on a feature of the landscape, letting her abruptly getting off the frame and the editing always segues seamlessly into the lives and the words of the others. The film eventually reconstructs her a dull downward spiral to physical decay and the wider context wraps her wanderings into a grim and death-like atmosphere – the winter weather, the cold light, or the plane trees slowly dying from a parasite that one of the people she meets, a scientist, tries to fight off.

She gives just snippets of information about her. Her name is Simone Bergeron but she rather likes to be called Mona; she has no longer any relative; she has graduated from the high school and has worked as a secretary. That is all, and the film never tries to investigate further. Her transition to a vagrant life remains wholly unexplained; the few comments she makes about this new life, usually delivered either in bad temper or in an offhanded manner, emphasize what her attitudes show: a primeval, basic, radical rejection of customary rules and a fierce embrace of freedom and solitude. She wants to live without a roof and without a law (this is the meaning of the French title, the English title being “Vagabond”). Either you accept this or you just go to hell – and the audience must deal with this awkward character in these stark terms while director Agnès Varda never attempts to flag her opinions or sentiments. It is true that she is too busy capturing as they come the words and gestures defining Mona who is played with stunning fierceness and sensibility by actress Sandrine Bonnaire.

Her transient and tragic story is described with an amazing accuracy and full respect for her choice. It is such a stunning, scandalous move that it cannot leave people unconcerned, and the other part of the film, the flow of comments and actions by the people who have met her, explores how the enigma of Mona can be grasped. Ironically for a person so keen on solitude and movement, despite the risks (that the film rigorously highlights), she does leave a trace in the hearts and minds and her adventures elicit remarkable reactions that turns her story into a wider reflection on society and individual expectations. If some judgments are predictably moralistic, many are more complex and open a discussion on what freedom actually mean (in particular for women), on the relations between the mainstream and the fringes (the film touches upon the issue of migrants and their precarious situation), and what love is. The range of sentiments is wide but “Sans toit ni loi” deftly shows that actions and words can belie the claims of fairness and coherence. Mona’s one-track mind compels the audience to question their own prejudices about social and individual ethics. The tour de force is that this demand is not imposed by a director’s viewpoint but spawns from the quiet and frank conversational mode she has chosen to tackle this enigma of a person.