Italy, United States, France, 1971

Directed by Luchino Visconti

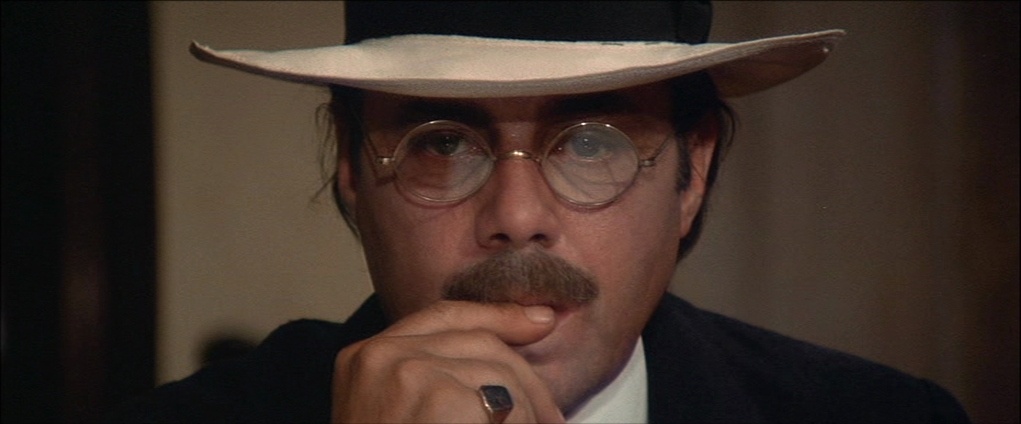

With Dirk Bogarde (Gustav Von Aschenbach), Björn Andréssen (Tadzio), Silvana Mangano (Tazio’s mother), Mark Burns (Alfred)

Gustav Von Aschenbach is a dapper and distinguished middle-aged German musician. But in the first scenes of the film, he is above all a fussy, cantankerous traveler, a frail, nervous fellow, the kind of upper class man always complaining about service, and bemoaning the weather. He cuts both an ordinary and lonely figure in the sprawling lobby, huge rooms, long corridors of the Venetian grand hotel where he is staying, another sophisticated and wealthy patron as idle and aloof as the others, with the same luxury tastes and precious ways, but unlike most without anyone to accompany him, and no one he can relate to – except that strange, gracious teenager who dreamy eyes and lively manners stand out, at least in Von Aschenbach’s eyes, as showed in a remarkable, endless roving of the camera, panning left or right and zooming in or out, during the first evening of his stay.

Which he cuts short. The few days spend at the beach, observing with growing intensity the young man who is named Tadzio, the elder, and actually the only son, of the many children of a lady who seems to be Hungarian, do not satisfy him truly, in spite of the fair weather, the dedication of the hotel’s staff, and indeed these dreamy eyes and lively manners that also thrill the other teenagers and children on the beach.

So off goes the grumpy, sickened, musician. But it turns out his trunk has been put in another train that the one set for Munich. That gets under his skin: he makes a big fuss and the capricious move not to leave the city till the trunk is not back in his hands. But the man sailing back to the grand hotel is not at all annoyed or sorry – he smirks all the way, glad that fortune plays a trick on him and the other way around (after all, the trunk could have sent to Munich later, and without much trouble or delay). He savors the opportunity to observe again Tadzio.

But his pleasure is spoiled by worrying signs of a health crisis, stern warnings posted on the walls, rumors running in the corridors, a shocking conversation with a travel agent: plague is lurking in the streets, it seems. And there is another problem: even as he gets mad about Tadzio, social conventions, the difference in age, just common sense, make it impossible for Von Aschenbach to entertain any relationship with the teenager, who is clearly aware of the German’s excitement, but never seems interested in getting in touch. Days go by, the city becomes an increasingly unsafe and dangerous place, Tadzio becomes more and more exciting and untouchable, and eventually Von Aschenbach collapses, death providing the bitter, dismal conclusion of a second stay that should not have been, the voyage to light proving to be a tour in hell.

Von Aschenbach’s narrative arc is thus a huge, cruel irony. He traveled, as the first of a long series of flashbacks providing background to his strange story points out in dramatic fashion, to keep health and also sanity. But he is so restless and fastidious he cannot find them in most concrete ways. And he is seized by an incredible obsession that drives him to make a fool of himself and then to get sick. The promise of a fresh breath of life ends with despair and death. And perhaps when he collapses one dark evening against a fountain, exhausted by a walk he started only to tail Tadzio and his family, just like a teenager would have followed the object of his desire in other, more childish and romantic circumstances, and begins to laugh, and even to guffaw, he may be getting fully aware of that irony his Venetian adventure is now.

Flashbacks fall in two categories. Those appearing before the incident causing that doomed second sojourn are focused on talks, or rather tiffs, he had with fellow composer Alfred. These deeply intellectual conversations tinged with stubbornness and sarcasm depict a chasm between the two friends, with Albert claiming Von Aschenbach is stuck in a definition of beauty and art too lofty and high-minded, too astutely removed from the life and emotion coming from a harsh but riveting reality, too concerned with the dubious and paralyzing notion of purity. This judgment informs the moral, spiritual tragedy hitting Von Aschenbach – in a way, Tadzio, and the idea of being with Tadzio, stand for a raw beauty and exceptional emotion that the composer never accepted as possible in his creative work. The Venice journey is the belated revelation that he spent his life setting goals that were as cold and irrelevant as Albert suggested.

And gladly insisted on his point near the end of the film, at the very end of the second series of flashbacks scattered over the tormented sojourn of Von Aschenbach, as his fellow musician has just been hissed and booed by the audience after the debut performance of a new work. Those glimpses on the past show that the man who is wandering in Venice used to be a self-satisfied bourgeois, with a wife, a daughter, success. But he lost his girl, had a relation with a prostitute that led to nowhere, and finally that public rejection of his raison d’être. Interestingly, nothing in this past suggests another kind of love and sensibility could appeal to him – but the case of Tadzio is less clear-cut, as he frolics with a young brown-haired, warm, seductive boy, a playful friendship clearly redolent of homosexual intimacy. However, his history has been so painful and disappointing that he may be far more open to bold, amazing adventures than he ever thought. His pious kissing of the old photographs of his late daughter and vanished wife emphasize how haunted by this past and his moral standard he vows to be – but minutes later his eyes rove and meet Tadzio’s face. However, time may already running out.

One of the first things that appeals to him when he arrives in Venice is the madcap, vulgar words of greetings and cheering of a man slightly older than him, dressed in white, his face looking like a clownish, dubious grimace, as if too much make-up was put to mask age or to appeal to others, a grotesque display of cosmetics that would rather fit an old prostitute. Such a face appears after the beginning of the second part of his travel, slightly less coarse and clearly younger, belonging to a street singer who would, like others, lie to him when asked about the health situation in the city. The most surprising turn in Von Aschenbach’s infatuation with the young Hungarian, and the most scathing aspect of the irony he lives through, is that he would accept that a barber takes care of him so to get a make-up, a travesty of face, that outrageously suggests he is far younger and finer than he actually is. It is as ridiculous on him as it was on others, of course. And it pathetically shows how much he has lost all control: even as all hell breaks loose around him, he is behaving as a loose character, doomed to fall – this is again this splendid sequence when he stupidly tails Tadzio, stumbling in deserted streets where fires burn to blow away pestilence, till he falls against the walls of a fountain, terrible nocturnal shots captured by a gorgeous cinematography.

This image matters to gather what happens to the lead character, and so are many others that were carefully composed and would be till the final minutes. Despite the amazing crowds moving around, the bustling life of the city, the details of the life of a grand hotel, elements painstakingly chosen and arrayed, powerful shot, vibrant testimony of a grandiose period piece keenly prepared and managed, this is a silent film. Von Aschenbach barely speaks, and certainly not to himself, cannot anyway confesses, never writes his thoughts, which are not expressed by any voice-over. Even most of the flashbacks only display his reserved attitudes as he deals with death or luxury. The existential crisis of Von Aschenbach is not articulated, just felt trough gestures, looks, behaviors. His story is about a man whose real physical pain gives way to a plight born out of an unexpected torment, an earth-shaking moral, psychological, aesthetic challenge that overwhelms him, something he had never been prepared to, something he would not have believed in, and something he would struggle to analyze properly, with the right words.

Mirroring him, Tadzio cuts a very quiet, eerily gracious figure, a remote but lively character beckoning to Von Aschenbach, aware of the feelings he elicits, but still concerned with himself. Actually, “Morte a Venezia – Death in Venice” brings to mind the silent era, through a peculiar slow pace, those deeply expressive performances, and an exquisitely crafted, increasingly dramatic atmosphere (and it gives Dirk Bogarde the opportunity to put on one of his best performances ever).

Von Aschenbach’s story is also about the poignant failure to have, and deal with, a view on the world. He led his career and life stirred by conservative, bourgeois, idealistic images, but they failed him. In Venice he tried to find something new: his eyes pored over the place and did find a stunning image. But he floundered as he attempted to appreciate it, and even degraded his own image. But it was too late. The heartbreaking finale, pitting the musician suffocating under the heat, the dark dye of his hair leaking over his unnaturally white face, against the teenager striking a Grecian pose in an amazingly shimmering, warm luminosity, shows that the genuine and upsetting image of beauty and life that should have guided him would forever escape him – a final irony, a terrible failure, the end of everything.