France, 1977

Directed by Agnès Varda

With Valérie Mairesse (Pauline), Thérèse Liotard (Suzanne), Robert Dadiès (Jérôme), Ali Raffi (Darius), Jean-Pierre Pellegrin (Pierre Aubanel)

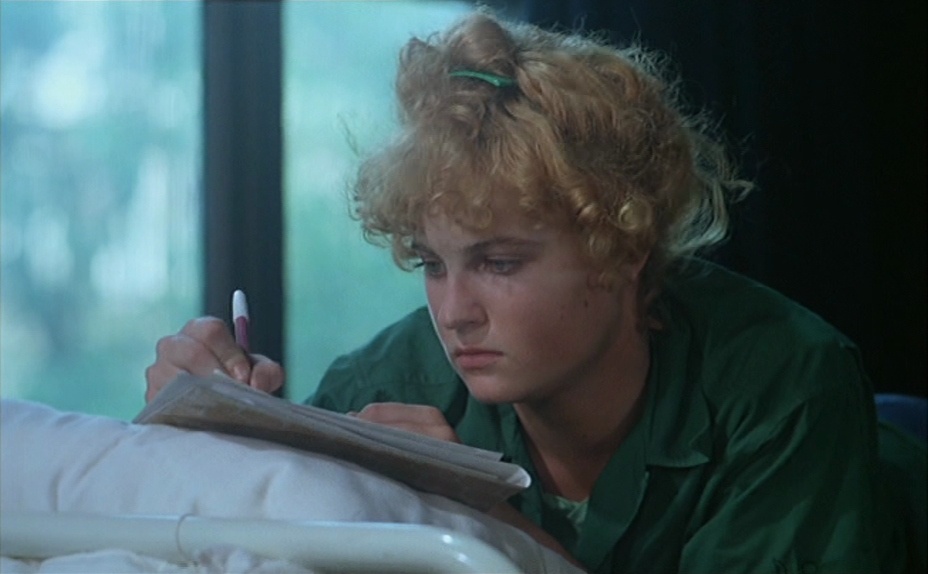

The prologue takes place in the drab streets of Paris in 1962. Pauline, 17, chances upon Suzanne, 22, a former neighbor whom she liked but who had to move away. Both face problems. The former, a high school student, dislikes the bourgeois and conservative way of life of her parents and formal education while the latter, a housewife, is exhausted by her family life: she must look after a male baby and a female toddler and do all the household chores while her husband, Jérôme, a photographer, struggles to make ends meet; moreover, she is again pregnant and just cannot accept to have a third kid. Pauline steals money from her parents to pay Suzanne an abortion, which drives her to break with them. Soon after Jérôme hangs himself, leaving Suzanne alone and penniless. Both friends part ways as they must grapple with their own fight for survival.

In 1972, Suzanne and Pauline meet again by chance on the fringe of a demonstration against the legal ban on abortion. They vow to stick together but the career paths each has embraced in the course of the ten previous years stand as an obstacle. Nevertheless, they stay in touch by writing postcards; they keep thinking of each other; and finally, Pauline, who is always travelling, would visit Suzanne’s house in the South-East of France. In 1977, the time of the epilogue, their bonds are stronger than ever.

That long narrative is strikingly elaborate. It chronicles in detail five years of these women’s lives but in a first part features flashbacks explaining how they asserted their positions in the society. It is told by two and then three voices: voice-over takes up a great part of the soundtrack, but the memories and comments of Pauline and Suzanne are increasingly completed by the information provided by a female narrator, who is the director; in the epilogue, the narrator takes full, omniscient control, telling the audience what befalls to all the characters, not only the leads but also the others who have become their true friends, even if they have briefly featured, and drawing her own conclusions.

It also spans a wide geography as it deals with women who have always been on the move, one of them eventually settling down while the other is still wandering: Suzanne lives in Hyères, where she is a secretary for the Planned Parenthood movement, but goes to nearby Toulon and had to spend tough years in her native Soissons; her bohemian and bold friend has kept living in Paris but hits the road after 1968 with an all-female, hippy band, the Orchids, achieving her dream of working as a singer and touring many rural areas, goes to Amsterdam to get an abortion and then travels to Iran to please her lover Darius, who is from the Middle East nation and convinces her to marry him there. It is an ordinary fiction deriving from no specific genre but has the elements of a musical. It is full of funny lines, poetic images and astute cuts but the camera can have a distinct documentary feel.

“My body is mine”: the line features in a song Pauline and the Orchids often sing, a performance that is a leitmotif – for Pauline and for the film, singing not only illustrate life but also purports to awaken minds. In this labyrinthine, eventful and playful narrative, the female body is the nexus and the focus. Asserting the identity, integrity, freedom and well-being of that often-coveted and cliched body is what is at stake in the heroines’ political fight and individual fates, giving the film its peculiar edge.

If Pauline gets reunited with Suzanne it is because her attention has been caught by stunning black and white photographic portraits of sad women on display in a showcase – it turns up the shop is Jérôme’s studio and that his collection includes frontal nudes. Pauline would also pose in the buff for him, to no avail as she cannot inspire him. He strives to capture women with their guards off, fully exhausted by their daily trudge, supposedly ripe for letting their true self out. Pauline is a far more independent and spirited than most of her sisters, it seems. But these pictures also allow Agnès Varda to quietly show the female body in a plain, quiet nature, putting it at the center of her vision. In 1977 she benefits from the porn vogue making it easier to screen naked bodies but her images pointedly refuse to cast women as objects of desire or topics of intellectual critique (Jérôme’s wish).

The battle for abortion, who raged in the 1970s in France (the film is shot just three years after a vote legalizing the practice) and in the wider Western world, is the prime battleground for defending the liberties and identities of women. The film deals with it with a clear sympathy for the women needing it, in particular the group Pauline is part of which had in the 1960s to travel to Amsterdam to get it, a wonderful sequence spurred by Pauline’s memories and built around one of her first songs (the lyrics of the songs, as well as the dialogues and the screenplay are penned by Varda).

But the film does look at motherhood more positively. It dwells on the satisfactions Suzanne draws from her kids, even when her Soissons-based parents have made their lives cruelly difficult (there is this chilling moment when her mother announces the lunch is ready: she doesn’t yell it to everybody but tells Suzanne in a cold, low voice, that everything is ready for her bastards). And there is the confrontation with the Muslim world: Pauline discovers a society where women live wrapped in clothes and separated from men, which disturbs her but at the same time awakens her to what a female body is also expected to do. She decides to have a baby – she would even manage to get another one, even if her love affair with Darius end up in a disaster. Pregnancy is not always a problem but also a natural desire and what raises questions is the social attitudes toward women. Nothing less and nothing more. It is worth noting Varda shoots Iran with a striking sensibility for light and colors but still observes this society in a clear, nonjudgmental and documentary-like manner.

“L’une chante, l’autre pas”, one sings, the other does not. The differences between Pauline and Suzanne run deeper than that and yet are not so big. Both, five years apart, attempt to claim their own, rightful positions in the modern society as modern women. Through art or through an activist job both fight to advance their ideas on women the problems they met have plainly shaped. Pauline is a perkier, more adventurous character while Suzanne is more focused on the distaff side and more contemplative. But Suzanne’s quest for love proves to be a relevant questioning about the way to build a relationship to find respectful harmony. If she rejects at first the flirt of Doctor Pierre Aubanel it is quite not out of the conventional, moralistic concern he is already married; principles do no matter as much as the dubious ability of the man to be fully with her and attuned to her. Here again, the audience is called to reflect upon the male attitudes in the light of a pressing demand for acceptance and respect of more modern, confident and independent women. Fighting for the body is also fighting for a sensibility and an ideal.

Pierre would understand the point, tough belatedly. On the other hand, Darius comes out of the film more like a hypocrite: he remarkably fails in Tehran to act upon what he thought in Paris. But those men are not fully condemned by the film. What also holds the complex story together is the incredible generosity of Varda for people and places. She deftly and gently captures the 1970s zeitgeist and the various viewpoints at play to show a changing society and two changing, endearing personalities with a kind and detailed attention to the contradictions, the mistakes but also the passions and the patience of the characters and the people around them. Her gaze goes deep, it is unfailing, it is faultlessly attentive and that helps the whole story to unfold fully and the film to stand as a thoroughly honest and vibrant portrait of a new and perhaps stronger feminine identity.