France, Japan, 1959

Directed by Alain Resnais

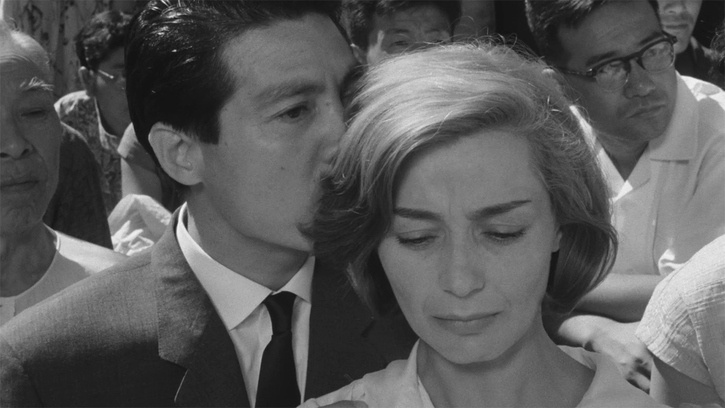

With Emmanuelle Riva (the woman), Okada Eiji (the man)

It takes some time to grasp the astonishing audacity of the movie’s first part. The editing blends abstract, stylistic images of torsos hugging each other, with their arms endlessly grappling, extending, folding, with images of Hiroshima and of the victims of the atomic bomb dropped on the Japanese port in August 1945. The soundtrack features the voice of a woman describing what she saw in the town and is illustrate by disturbing, dreadful pictures from both the present and the past; she is interrupted from time to time by the voice of a man who has an accent clearly indicating he is not a native French speaker, unlike her, and is keen on dismissing her recurrent claim – no, she saw nothing in Hiroshima. The images on the naked bodies crop up oftener and oftener, then the frame widens and the words change, sounding like the talk of lovers who have just made love and then picked Hiroshima’s reality as a topic of conversation.

This mix between a tragic, earth-shaking historical fact and sexual intimacy is wonderfully shot and edited but deeply stuns. The film keep surprising us: if it appears the lovers’ story takes place in Hiroshima, making their conversation more logical and inevitable, it turns out it is a one-night stand, the woman having drawn the man into her hotel room. Both are married and engaged in casual sex just for the thrill. Their background are completely different: she is an actress from France taking part in the shooting of an international production about Hiroshima; he is an architect from Japan and the port was where most of his relatives used to live. His willingness to carry on with their affair is as passionate as it is awkward but his goal seems as improbable as their situation has already been.

But she accepts to see him again and that new evening spent together in a bar brings the astonishing fictional drive of the first part to another, deeper, more unsettling level. If she was previously bearing testimony to the devastation around them, she now slowly makes a confession, answering his prayer to know her better with amazing sincerity. For the first time she explains to a stranger that her first love, years ago, back in her native Nevers (a small town in the middle of France), was a German soldier, member of the Nazi armies controlling then swathes of the country. For the first time she felt passion and desire but that ended in full disaster: the soldier was killed and she was publicly humiliated, her parents forced to hide her away in a cellar as she turned insane for a few weeks.

A brief, mysterious shot on a dead soldier had strikingly featured earlier in the after-sex dialogue of the illegitimate couple: now it stands as a herald of that long, depressing, poignant dive into a past that was painful for her as well as for her native country. The episode has a powerful, disturbing echo to the first scenes: it seems no human, even in their most intimate experience cannot escape the horror of History. It leaves an indelible mark that somehow creates strange bonds.

The third part is a long perambulation through the night and the city. Images of Hiroshima and Nevers get mixed as she desultorily walks to find comfort, the man she once more rejected tailing her until they take another drink and acknowledge their true identity, as living embodiments of places where History killed and maimed and caused despair. An impressive vision of Hiroshima, with amazingly sophisticated compositions, that section highlights the emotional contrast between a man who has become obsessed with a stranger and is yearning for a full understanding of her and a woman who ceaselessly wobbles, tugged by opposite but deeply felts sentiments and still uncertain about the ways she could grapple this wreck of a life – a bewildering compliment she pays to the man points to her odd way of thinking and feeling: “You are killing me. You are doing me good”.

A radical and philosophical viewpoint on the human suffering over the course of the terrible World War Two, “Hiroshima mon amour” blurs the lines between time past and time present, East and West, and challenges the differences between immediate satisfaction and legitimate commitments, the persistence of a searing pain impossible to share and the urge to connect deeply and forever. Unnamed and just defined by the burden of their lives and national histories, the woman and the man, however, never feel as just abstract expressions. The first vision the film gives of them is after all their naked bodies furiously embracing; the gazes and attitudes they have in the final part, including the powerful last shot, convey deep and genuine sentiments that mesmerize the watcher. The performances are not just an unnerving, distant expression, using incredibly repetitive, literary, demanding lines – the faces and energy of Emmanuelle Riva and Okada Eiji have a genuine ring, a lively edge that makes their characters wholly fascinating.

The screenplay and lines were written by Marguerite Duras, a leading writer who attracted attention with “Un barrage contre le Pacifique” in 1950 and avant-garde works like “Moderato Cantabile” in 1958. Her special bond with Asia and her quest for a novel expression of the female experience obviously shaped her text which claims that victims of war carry always the same burden and pain no matter what their native cultures and political contexts are while analyzing the impossibility for an individual to forget past horrors and to put them fully behind them.

For his part director Alain Resnais, a contributor to the nascent cinema movement of la Nouvelle Vague, was famous for shorts whose style was bold but whose contents were censored – in particular “Nuit et brouillard”, in 1956, about the Shoah (and the role played by French authorities in that genocide). He wanted to go further, with a longer film dealing with the atomic bomb. Relying on an earlier, groundbreaking and poignant effort by a Japanese filmmaker, the 1953 feature “Hiroshima” by Sekigawa Hideo (some images of the Resnais film are actually borrowed from that production as well as a lead actor, Okada Eiji), he eventually shot and edited this incredible film which distorts a love story told at the present tense to investigate the power of memory and ordinary people’s struggles to grapple with the past and to reach eventually a desired sense of completeness and love.