India, 1977

Directed by John Abraham

With Srinivasan (M. B. Narayanaswami), Swathi (Uma)

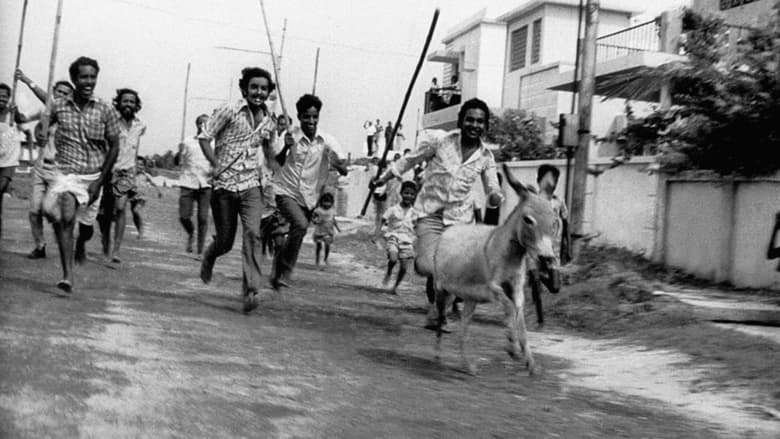

Narayanaswami is a university professor, teaching philosophy in a Brahman colony in Chennai. He finds one day on the doorstep of his bungalow a young donkey – the new-born animal has just become an orphan after a bunch kids took on its mother, harassed it, and chased it around till the animal got so wild and the kids hysterical that an angry mob decided to hunt animal and kill it.

Narayanaswami vows to take care of the donkey. But his maid grumbles at the extra work and he becomes a laughing stock for his students. Under the pressure of the university’s management, he decides to bring the animal to his native village, trusting the beast to a young mute woman, Uma, who is close to his parents.

But when he travels again from the big city to the quaint village a few months later, Narayanaswami is forced to listen to his father’s long account of the many incidents the donkey has supposedly caused. There are may grievances, especially from the Brahmans who perform the many rituals their faith demands for the well-being and the harmony of the community. The professor is dispirited, but still thinks the donkey can stay around and live peacefully.

Another few months pass, a new trip is made, and things decidedly do not look up. New stories about the beast’s mischief are told to him, this time from Uma, who tries to take the troubles light-heartedly and who is now, in a surprising development, pregnant. But another voice is added to the chorus of complaints: the wife of Narayanaswami’s brother cannot stand the animal and the ridicule it brings to her husband’s family. Still, Narayanaswami keeps thinking the animal is safe.

A few months later, he finds out he was wrong. The donkey has been massacred like his mother, blamed for a shockingly impious action that cannot be condoned: Uma’s mother claims it carried to the village’s temple the body of her daughter’s still-born baby. The Brahmans felt they could not do less and otherwise. But in a new amazing development, they start to see the ghost of the donkey. And they realize this ghost can work miracles. So they determine that the village and the temple must worship the animal they so quickly killed.

Narayanaswami, who is baffled and incensed at these fresh, astonishing developments, and Uma, still grieving her baby and now a deeply upset and saddened character, who would never smile nor keep clean and smart (the contrast is stark between the neat hairdo she had for most of the narrative and her new, terribly disheveled look), take part to the ceremony turning the skull of the donkey into a hallowed relic: but things go awry, and the fire of the ritual causes the destruction of the whole village, with the mute girl and the stern lecturer standing as the silent, hostile witnesses of a disaster that they probably feel justified and certainly no cause for mercy.

In a conversation with a student about his new, implausible pet, Narayanaswami asks the nice young wan whether he has ever watched a film called “Au hazard Balthazar”. Director John Abraham cannot make it plainer that the 1966 masterpiece of Robert Bresson was his inspiration and the basis of the screenplay. Like Balthazar, Narayanaswami’s donkey wanders in the countryside, buffeted by men’s wickedness despite the love and care of a quiet, kind young woman, and is readily associated with a spiritual, redeeming view of the world. But the Indian filmmaker delivers an ever broader view – the adventures of the donkey start in the capital of Tamil Nadu – and a far more political and scathing one, which is peppered with bold cinematic ideas that have little in common with the aesthetic asceticism of his French counterpart.

The foolish ways of the university’s young men foretell and mirror the vicious ways of the village’s kids and if the students go too far when they pitilessly rag their teacher, the other educated men the donkey must deal with, the wise and old Brahmans of the village, prove to be disingenuous and dishonest beyond belief. The reconstruction of the events blamed at the donkey by a dynamic, precise camera clearly show the beast was prodded to mess around by the kids, to make a prank often, and in one cast at the bidding of, surprise, a Brahman eager to ruin a wedding: but never do the wise men consider the possibility of a human action. They even end up giving credence to the unconvincing tale of Uma’s mother – mainly because they have always wanted to get rid of a beast they deemed unfit for an educated fellow villager who made his way in the big city.

Narayanaswami is exceptional, truly: his social background and his scholarship do not keep him from having a kind view of the lowest forms of life and of the less successful people, as demonstrated by his deep sympathy for Uma he sometimes seems to like even more than people of his own kind and clearly wants to help far more. By putting his gentle attitude, bold choice, and ultimate sorrow front and center, shot in a delicate, compassionate manner, “Agraharathil Kazhuthai” makes him genuinely relatable, and invites the audience to look at the rest of the characters far more critically – the satire of the upper caste and religious and social prejudices is thus made even more stronger, personal, and withering.

Uma becomes a victim hard to forget: when she appears after a long absence on-screen following the birth of her baby, she is shot against the light, her back a dark mass catching the attention, and when she slowly turns around and reveals her face which then takes up the screen her despair and anger are plain and shocking, so a world apart from the smiling girl the audience has been used to watch. She is first the victim of a fellow villager who has seduced her: the tale of this reluctant romance is wonderfully shot and edited by the director, the regular comings and goings of Uma between fields and the house of Narayanaswami’s parents where the donkey sleeps and where the professor has long talks with his dad turning out to be the occasion the villager chooses to court the girl, with each new round of walking showing the progress of his courting till a beautifully, skillfully elliptic sequence where he makes love to Uma.

Uma would then be the victim of stupid prejudices: first her beloved donkey is blamed for her still-born baby and then it is killed, before the killers change their mind abruptly. Once again, the donkey was not to blame, she was just the victim of a misfortune that health can sometimes cause, a natural tragedy – the shots of her delivery are interspersed with slanted, spectacular shots on a cacti field, perfect symbol of the risks of child-bearing and of course of a reckless love affair with a lustful and irresponsible man. What happens next just underline how fickle and irrational the upper caste can be, even as the lower folks are doomed to grasp with harsh realities on their own, unable to rely on power and knowledge, elements that can be blatantly misguided. No wonder that Uma looks at the final fire unmoved and harshly: it would be hard to find any ground to forgive such a community that was so cruel to her, her dear donkey, and her benefactor from the big city.