Sweden, 1969

Directed by Bo Widerberg

With Peter Schildt (Kjell Andersson), Kerstin Tidelius (Karin Andersson), Roland Hedlund (Harald Andersson), Marie De Geer (Anna Björklund), Olof Bergström (Olle Björklund), Jonas Bergström (Niesse)

Kids are playing, in a way that is as thrilling to them as worrying to us, perched on the long roof of a barn or trampling around the big heap of straw they made, trying to fly like birds and then like airplanes, thanks to flimsy frames they assembled from sticks and fabric. Teenagers have gathered in an abandoned house to play jazz, in tune with what an old-fashioned record player blares, rather poorly as they are using makeshift instruments made up of everyday utensils, from pipes to brooms. Adults are loitering, poking fun at a mate who is way too partial to beverage. A woman cleans her house, washes her laundry, teasing her toddler.

Blissful pictures of a sunny spring in a corner of Sweden between the two world wars: life as quiet and nice as it gets, captured by a splendid cinematography (a delicately soft and warm light, smart framing) which effortlessly highlight authentic and lively performances. It is just a few lines exchanged well into the film and very casually by the drunkard and Harald Andersson, the husband and father of the family at the center of the narrative, that disclose how tense and tough the situation is, with a long and bitter industrial action making life difficult and getting opposing positions even more entrenched.

This is the valley of Ådalen in May 1931. Factory workers have stopped working to show solidarity with strikers fighting in another area of the Scandinavian nation against a wage cut. The social conflict gets worse as no compromise seems possible between the stubborn workers, who command a real, huge popularity, and the companies, who have the understanding of the conservative government. In the valley of Ådalen troubles, despite the tranquil, relaxed images the film shows, are simmering, and soon get out of hand. The problem is that factories’ bosses decide to bring strike-breakers to get their goods dispatched, the best way to stoke the anger of the strikers. A confrontation between the two groups of workers raises the tension, including among the striking workers, as some regret violence while others call for immediate, positive results. Another clash, this time between strikers occupying a warehouse and the police, raises the stakes further and brings tension to fever pitch. Strikers decide to go to the town of Lunde to air their grievances and denounce the police’s violence. They are met in the road by soldiers tasked to keep them from moving ahead. And they do it by firing on the crowd, killing five, including a by-stander, a young woman.

Yet to deal with this historical tragedy, whose impact on the Swedish society was instantaneous and huge, forcing changes on the way police and the military can be used first, and then helping the Social Democrats to win election, starting a reign of more than four decades, director Bo Widerberg has not chosen to shoot a heavily dramatic and politicized, really stern and brutal film, which befuddled some at the time of the release. On the contrary, he emphasized a chronicle-like, trivial narrative, underpinning the period piece with the easily relatable genre of the coming-of-age tale. Most of the film is devoted to the feelings and adventures of Harald Andersson’s elder son, Kjell, a lanky, discreet, intelligent teenager who stands at the crossroads between various walks of life inside his community at this point in time.

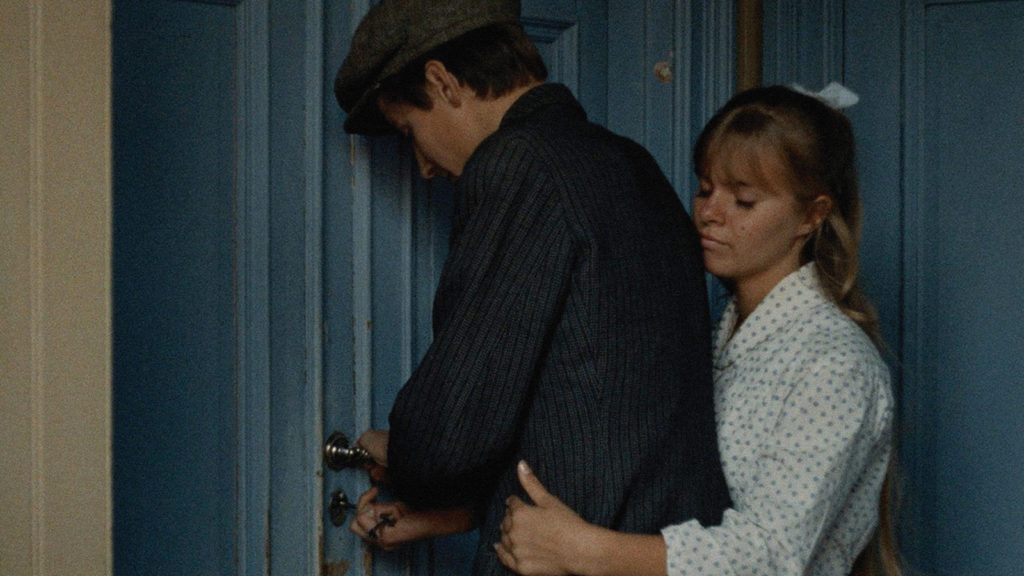

Kjell is the son of trade unionist who is on strike and of a housewife who symbolizes many domestic virtues and embodies tenderness, care, dignity – the radiant face of Karin Andersson is a wonderful watch, especially when she sees it to it her dear hubby is well clothed and her sons clean and happy. His best friend is Niesse, a mischievous teenager leading the jazz band where Kjell and others play, and also, like Kjell, a member of the orchestra of the local community (but not the most serious and punctilious), but above all obsessed with girls, the body of girls, and the mystery of sex. Kjell is interested in sex and girls, too, and is actually falling in love with the daughter of a factory boss, Olle Björklund, Anna – he knows her well because he is so bright and curious that Anna’s mother invites him to read books on art, in a case of a worker’s son getting acquainted by a bourgeois family, and perhaps getting absorbed by their culture and values, a possibility Karin Andersson is aware of, and perhaps worried of.

And she is right to be worried: Kjell and Anna make love, and the girl gets pregnant, a family drama that adds a new layer of challenges and conflicts to the wider narrative. The teenagers’ fault gets intertwined with the social crisis, echoing the social tragedy, furthering the antagonism, highlighting the deeper class antagonism. Anna is brought to a gynecologist in Stockholm by her mother on the same day that the demonstrations take their dreadful turn for the worse: as she is aborted strikers are shot dead, especially Kjell’s father and his best friend (in a blatant fictional rewriting of the events). Anna is shot asking Mrs. Björklund rancorously whether she is aware of what she has done to her and what it means; these same questions could arguably asked to both the police and military officers and their corporate bosses. The abortion and the fusillade make plain social classes cannot mixed, the working class being set to get mistreated, even trampled, to keep the power and prestige of the capitalist class safe and sound.

And yet “Ådalen 31” ends with a gay, vivid domestic scene, as Kjell cheers up his still-shocked, deeply mourning mother, stirs her into getting a hold of herself, forces everyone in the house to take part in a big clean-up. Smiles come back, window panes lose their dirt, and the youngest child playfully blow bubbles of soap, under the same lovely spring weather and nice diffuse light that have shrouded most of the film. It is with these images of mundane life, and real joy that the historical reconstruction is brought to a conclusion. It feels that for Widerberg, the point in dealing with this social scandal was to show how senseless and savage the deaths were, how absurd and appalling the crackdown was by contrasting the facts, handled in a clear-cut, concrete manner, with the ordinary lives of the workers, the small anecdotes that made their lives so worthwhile, so acceptable, so enjoyable. Widerberg emphasizes how decent and cheerful the workers were, quiet folks just hoping for tranquility and fairness, and he readily uses the tropes of the coming-of-age tale to make the audience even closer to the characters, clearly exploiting a kind of sentimentalism while avoiding a gritty, edgy approach. The outcome is unquestionably touching, reminding the audience that behind names and figures in newspapers’ reports and political speeches, they are genuine people with a past, relatives and friends, hopes and ideas, the taste for life and the appetite for love.