United Kingdom, United States, 1955

Directed by David Lean

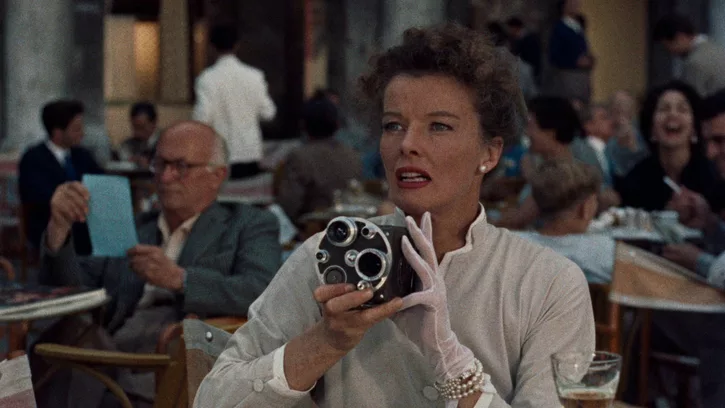

With Katharine Hepburn (Jane Hudson), Rossano Brazzi (Renato de Rossi)

There are a lot of typically picturesque shots in this story unfolding through the streets of Venice, some inevitably taken to impress with their stunning point of view – from the highs of a monument, for instance – and the lush Technicolor lends them a lovely brilliant patina. But they are not always postcards made for pleasure’s sake and to match the audience’s expectations on Venice. Shots are not always clichés, fortunately. Some simply capture what the lead character shoots with her own camera or watches with her eyes, while a few others focus on her perambulations. As this character happens to be a tourist, an American on vacation, these images in part suit well with her situation.

Yet this situation proves rather difficult to define. She has the same worries and practical reactions as any tourist, that is true, but she is adamant she is no tourist – indeed, the film humorously (and not on a subtle mode) contrasts what Jane Hudson is up to with the boorish and self-satisfied behaviors of a couple of Americans feting the retirement of the hubby with a European Grand Tour, guests of the Venice pensione, or little hotel, she has chosen. Jane Hudson has clearly dreamed of something upon arriving in the city yet she talks about it with the pensione owner as if she was reporting the thoughts of a person she has met. She prides herself of her independent streak but she is clearly uncomfortable (this is a real understatement) with being alone in the streets or in a café.

When she meets by chance a middle-aged antiquities dealer who has already noticed her in a café, she loses her self-control. Once she collects herself, she begins an odd relation with Renato de Rossi, even as his purpose is clear to him, and the audience, that is, to have an affair with her, in the most genuine and straightforward manner. She is afraid to share the sentiment and easily ruffles Renato de Rossi’s temper. They would eventually enjoy a wonderful time together but she will not make it last.

Apart from the physical evidence that she is middle-aged and lonely, it is very hard to gather who Jane Hudson really is and what her story has been so far, and she sees to it that no information is given. It seems nevertheless plain that her life back in the United States is dissatisfying and her past filled with disappointments. Despite her brash attitude, she is weak. Her Venetian adventure is not only about getting out of her home and routine, but also about filling her life with desire, although she is painfully aware she may have not the skills and grit required for making it a reality. This is the portrait of a forlorn and sad woman grappling with the diminishing prospects of middle age and the tragic fragility of happiness, but still keen on capturing the beauty of the world (hence her devotion to filming) even if she is unsure whether she can take play on the world’s stage (hence her demure and reluctant attitude), a funny yet poignant case of a character play-acting life but unable to feel it.

Katharine Hepburn was 48 when she played this part. Her previous feature had been released three years earlier. Her career in Hollywood has not been a pleasure cruise, in part because of her own independent streak (in this regard, a line she tells has an ironic resonance). This film looks like another opportunity to assert her talent even as she is aging, and indeed it requires all her feisty determination and sense of tragedy to make Jane’s character credible and likable, even as it is not glamorous and easy to size up. She pulls it off, helped by the precise and effective (and nothing more) performance of her Italian partner, Rossano Brazzi. Hepburn’s gaze, face, and demeanor convey with the right level of spontaneity and sincerity the forlorn and wistful nature of the unfortunate heroine.

The camera of of British director David Lean carries out quietly the task of illustrating this torment. He delivers delicately composed and lighted shots and his postcards, which genuinely feel like at times like love letters from a foreigner to the Italian city, also capture the moving, sometimes funny and sometimes heartbreaking, details of Jane Hudson’s reluctant, simultaneously feared and desired, romance. His Technicolor not only dazzles but reveals subtle feelings. He has at the end of the day crafted images that are a wonderful match and exquisite frame to Hepburn’s performance and Jane Hudson’s struggle to make the best of the remains of her life.