France, 1982

Directed by Chris Marker

He writes, she reads. “Sans Soleil” aims to record the experience of a cameraman traveling around the world and imparting his ideas and sentiments to a woman he loves living in France. But from the beginning the narration appears more complex than a simple reading of texts over edited pictures. The voice, belonging to Florence Delay, puts the man’s words in context as she releases her own information, using the preterit to introduce letters whose contents refer to what the cameraman shot as he was traveling and thus written in the present tense, that is the present time of his work. Moreover, the audience is watching those pictures as they were a film although they are yet to be edited to become a full-fledged feature. Time is on a slippery slope here while the man’s numerous reflections on life are echoed by what transpires from his work.

The film is more than a travelogue but not really a documentary reporting facts, although there are many anecdotes and historical digressions. As the pictures roll on, the cameraman’s thoughts keep expanding to bolder and more philosophical ideas the voice keeps track of. “Sans Soleil” is the record of a man freely and joyfully wandering across the globe and through cultures.

The film opens with a quote of Jean Racine, stating in the French version that: “The distance between the countries somewhat compensates for the excessive closeness of the time”; for the English-speaking version, director Chris Marker rather chose an excerpt of Thomas Stearns Eliot’s poem, “Ash Wednesday”: “Because I know that time is always time/And place is always and only place…” Time and place are indeed shaping the narrative as the traveler hops from one place to another, recalling various events of his life or the world history and as he goes meditative on the impact of time and cultural differences. The cameraman lingers in Japan for a while but also goes to Guinea Bissau, Cape Verde, the Parisian region, and San Francisco while musing on Japan’s actions during World War Two or the November 1980 coup d’état in Guinea Bissau. Nevertheless, he tends to focus his investigation on the distance between Africa and Japan, which are posited as two poles of the human experience with peculiar beliefs on history, death, and women.

Yet the first image shows three kids walking across an Icelandic landscape, an image the cameraman was unable to forget for its special meaning – so claims her voice: a fond memory of a personal past bringing happiness back in the mind. It turns out this image should have been the starting point of a movie but he failed to make it, just as he would probably fail to make the other one he talks about, a fiction about a man living in the 40th century AD. This would be a time, he imagines, when human beings have achieved a full command of their brains’ possibilities and have build a perfectly efficient society where forgetting would be impossible. But in this fiction a man becomes fascinated by the fact that in the past human memories were flawed and tries to understand what life was back then, rebelling against the very idea of memories getting lost. The spark for the cameraman’s imagination has been a rendering of a series of introspective songs composed by Modest Mussorgsky, titled “Sunless” – the very name of the film his pictures are now creating in a self-reflexive twist.

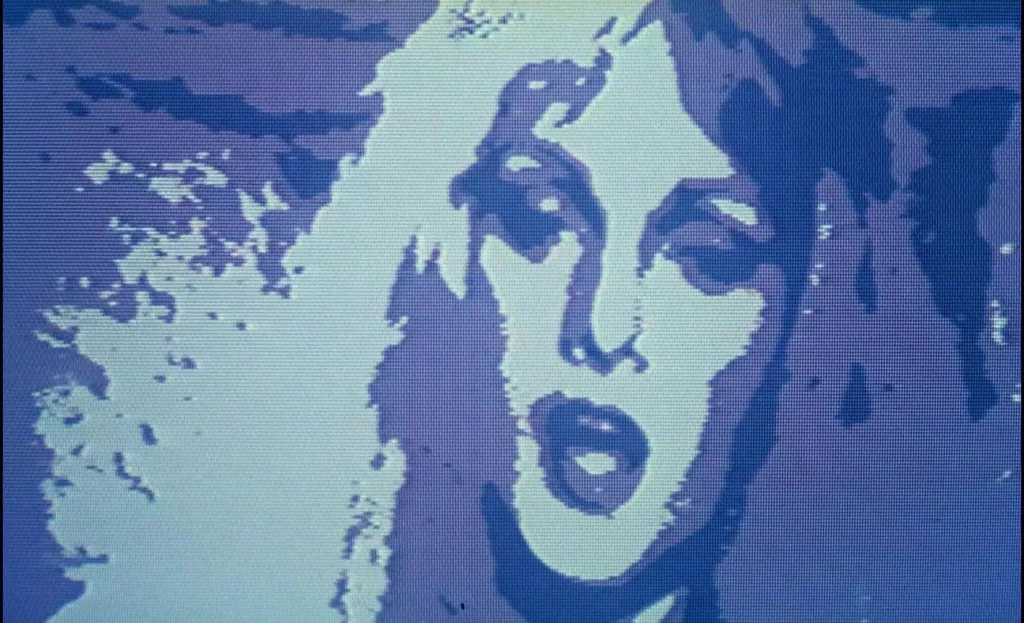

This fiction project points to a key fact. If the exploration of the cameraman has expanded to vast areas of lands and cultures, it also increasingly focuses on memory and time and how to show them. He explains that all his work has revolved around the importance of memory. He claims he could not remember things if he had not shot them first and depicts the ideas of a Japanese friend, Yamaneko Hayao, who thinks computers hold the key to safeguarding human memory and who processes pictures through a special software to create new images he believes to be even more genuine.

How to keep memories and what to do about them? The cameraman praises Japanese folk beliefs paying tribute to discarded stuff and disappeared cats, which are a source of inspiration to him while he readily throws doubt on the much-vaunted historical and political idea of a collective memory. To him political tragedies and historical analysis actually highlight the role of individual behaviors and sentiments. And old footage should always be watched with their wider context in mind, otherwise it would be crucially misleading.

He praises Alfred Hitchcock’s “Vertigo” (1958; he watched it nineteen times!) as a great movie on the fascinating spiral of time and the power of memory, as James Stewart is bewitched by a woman he spies on and gets desperate when she dies till he find another woman who looks like the dead and then tries to bring the past back, performing a resurrection of his own device, to his own risks. The cameraman himself tries to trap time as it goes by forever while pacing the streets of Tôkyô or the Sal Island’s beach, accumulating elements for films he knows he would not have the chance to make and still wondering what meaning he would get. Images and memory get intertwined and questioned through the delicately meandering ruminations of the cameraman and a stunning visual collage.

From photographs to file records and from clips of old movies to the nascent computer-generated imagery, the editing blends a riveting variety of pictures with the footage of the cameraman, whose hand-held camera scrutinizes the people and the landscapes it encounters. Editing has a baffling sense of the counterpoint, for instance when the story of writer Sei Shônagon is evoked as a Polaris rocket scuds across the skies or when portraits of Tôkyô commuters are mixed with excerpts from Japanese horror flicks. It is difficult to grasp and appreciate readily the breathtaking richness of the visual contents of a film keen on capturing the full experience of this thinking walker whose talks foster a film that is never acknowledged as being made and in fact points to other projects, a film that plunders existing images but imposes its own, flimsy, reality to the befuddled audience. As the cameraman follows his maze-like course over the world, its cultural representations, and time, the audience are confronted to a visual language suiting a new thought that are right now on the making.

The cameraman speaks highly of Sei Shônagon for her quest of a kind of poetry of the small things, expressed in wonderful lists of things, things to have, to avoid, or making your heart beat fast. In a way, the film’s intricate form echoes this poetic approach on life. The sinuous arc followed by the epistolary thoughts and variegated pictures looks like the personal line followed by a sensitive and sensible mind keen on communicating views shaped by their reactions to the world.

Elements and questions are listed as the man takes stock of his own human experience. As there are things to have, to avoid, or making your heart beat fast, there must be things that satisfy his own aspirations. The best he could settle for is that sense of poignancy about the transient things of life that pervades the Japanese culture according to anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss. And at the very end, our man opposes this cultural prejudice to the Western overconfidence on cultural knowledge and discourse. The fleeting images of the world which stream through this mock documentary bear testimony to its deeply chaotic nature and we would better look at them with attention and care to appreciate how fragile and contradictory humankind is and how essential respect is. The constant and mind-boggling, if spell-binding, disjuncture between various sorts of images, discourses, facts, lands that is the real heart and engine of “Sans Soleil” turns out to spell out a highly individual and coherent statement about a view on life and cinema essentially holistic and harmonious.

When he tries to capture how African women look in the eyes of men and cameras or when he buys a round to Japanese drunkards in a bar, the cameraman says he is striving hard to reach an “égalité du regard”, or “equality in the gaze”. At the end of the day, the film achieves to express an equality between the numerous experiences of the cameraman thanks to a magical fluidity eventually finding a sense of purpose. The cameraman’s journey ends up in the “zone”, the maelstrom of computer-generated imagery designed by Yamaneko, and named after the mysterious space the characters of Andrei Tarkovsky’s “Stalker” (1979) attempt to cross. Now stepping into a new audiovisual world that demands a new perception, the cameraman suggests we should take our pens and write our own Sei Shônagon-like poetry.

And why should not we try? After all, Marker has just given us a fresh look at the world and more importantly at the way it can be watched and assessed. The endless questioning about narratives his character – for the cameraman is actually fictional – raises and the challenging nature of the whole narration open our mind to the countless possibilities lying inside images and thoughts and invite us to start our own journey through them as well as through time, life, and lands.