(West) Germany, France, 1979

Directed by Werner Herzog

With Isabelle Adjani (Lucy Harker), Bruno Ganz (Jonathan Harker), Klaus Kinski (Count Dracula), Roland Topor (Renfield), Walter Ladengast (Abraham van Helsing)

It looks like they are eerie though disturbing statues but the more the camera lingers over the bodies and the closer it captures telling details, like a pair of shoes in relative good shape fitting the feet of lifelike legs, the more it rather looks like they are cadavers. The initial images are not a tour in a grotesque ancient place but a visit to a kind of spellbinding catacombs.

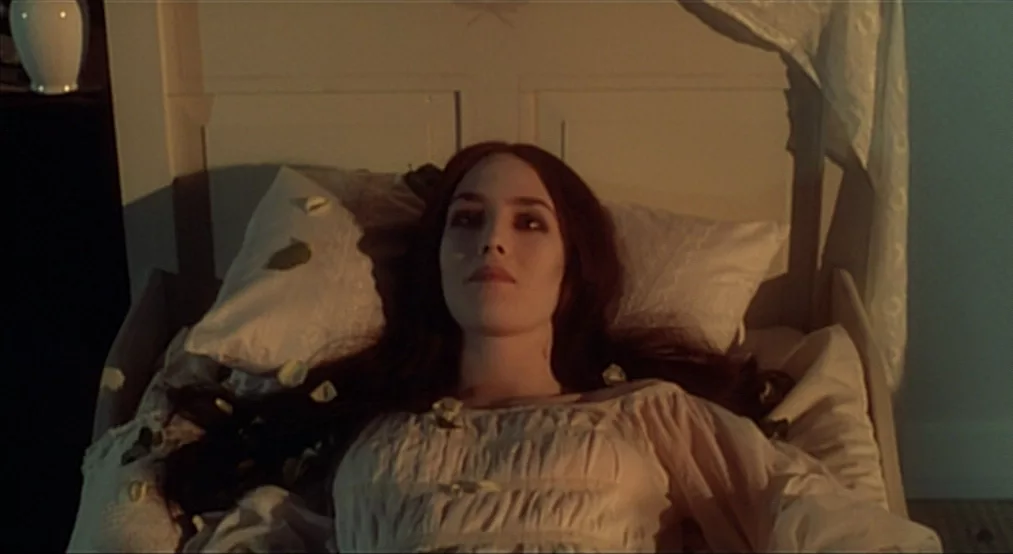

And then the editing cuts bluntly into a bedroom where a woman suddenly wakes up in her bed, rises her torso, and screams. Lying in the next bed a man rushes to calm her down and then lies down next to her in her own bed to help her falling asleep again. She just had a bad dream and should forget about it.

Things are not what they look: reality may well be a dream, or rather a nightmare, unless dream invades reality, what is alive or used to be could well be just death walking around, unless death is also shaping life.

And a remake may not be such a remake. Considering himself free from cumbersome copyright constraints and from the wrath of pugnacious relatives, which has famously not been the case of the great filmmaker he refers to, director Werner Herzog does not use the names contrived by Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau when he shot in 1922 “Nosferatu, eine Symphonie des Grauens – Nosferatu, A Symphony of Horror” but those imagined by writer Bram Stoker in his landmark novel “Dracula” and, while crafting the plot developments, follows at times more closely the source text than the source film.

Still beginning in a quaint little town more reminiscent of 19th century Germany than of the United Kingdom of the same period, the film surprises by highlighting so searingly how anguished Lucy Harker is despite the love of her husband Jonathan Harker, not just by illustrating a grim night but by associating to the female character a strikingly unnatural pallor and stiffness in gestures (although not in emotions). The whole German, mundane episode, emphasizes how pleasant and tranquil life is for them, with titles introducing lovely kittens and astonishingly white light bathing the domestic and street scenes. The contrast cannot be starker when Jonathan Harker gets the order from his employer Renfield to leave the town right away for Transylvania to negotiate a property deal with a mysterious but wealthy Romanian aristocrat: the boss lacks poise and decency, his gestures and tics suggest craziness, his office is depressingly dark and stuffed. This is enough to hint at future troubles but oddly Jonathan Harker keeps cutting a distant figure, taking things in stride, still conveying a stiffed confidence and an unshakable balance that makes you doubt if the character would ever feel really alive and reactive.

The journey to Transylvania owes as much to the sources than to Herzog’s own work, starting with “Aguirre, der Zorn Gottes – Aguirre, the Wrath of God” in 1972. Even if the villagers and Roma folks Jonathan Harker meets constantly warn him and convey the unnerving presence of a terror, the journey to Dracula is less frightening than fascinating; carried out partly on foot (in contrast to the book and previous film adaptions), it reveals a gorgeous nature tuned to the majestic overture of Richard Wagner’s “Das Rheingold”, a music highly inspirational and not really disturbing soon to become a motif of the film’s soundtrack.

Herzog actually becomes more and more personal in his approach even as he depicts the expected terrible moments, from the first appearance of the vampire in his castle to his arrival in the German town. Not only he deals with movements and travels with sweeping images evoking adventure and challenge but he barely insists on horror – this Jonathan Harker may have his blood sucked but he is never lured by strange female creatures or assailed by odd bats while the ordeal experienced by a sea captain gets a short shrift, the splendid images of a boat sailing through the seas or the voice-over of the captain as he writes down notes on the logbook seeming far more important and inspiring to Herzog than making a fresh attempt to create graphic images of terror. What the editing emphasizes is rather how the danger faced by Jonathan Harker is echoed right away by the worries of his wife, keeping exploring the deep-seated anguish of the female lead character that so powerfully opened the film.

It is after Dracula has landed in the German small town that Herzog gets bolder and careens off the trodden paths of the story as readers and moviegoers used to know it. He is followed by Jonathan Harker, but far from having recovered from his Transylvanian trial he is sick, suffering from anemia and amnesia – this male lead character is denied any agency and remains a powerless and irrelevant victim. The other male figure to emerge is only slightly more effective: doctor Abraham van Helsing is a cautious old man sticking to the science he knows, promptly overwhelmed by the events, including the plague epidemic set off by Dracula. Unlike his predecessors on the written page and the silver screen, he would never rise to the challenge, standing as the unquestioned authority professing rational views and old ideas, never grasping the eeriness of the situation and never trusting the words of worry and prophecy articulated in such a heartbreaking and determined manner by Lucy Harker. Even when the worst happened to her but also the best to the town as her courageous move hastened the end of Dracula, this Abraham van Helsing keeps cutting a foolish figure and his eleventh hour endorsement of Lucy Harker’s convictions about vampires and evil does not only look clumsy and contrived but also ironically draws him into a mess.

Fighting Dracula is in fact a lonely struggle Lucy Harker carries out with a passion born out of fear for herself and deep sorrow for what happened to her beloved husband, even as plague sows panic and disorder. She is the one who gets a fast-track education on vampires, the one who wants to awake the consciences and to help her town, the one who stands ready to challenge the all-powerful and utterly destructive creature. And she is eventually, through a personal sacrifice cleverly planned, the one who makes Dracula vanish. The film thus grants a female character whose position and import have in the past varied but have always been carefully limited to the benefit of the male characters a striking agency: more than the object of fascination to Dracula, Lucy Harker, who remains through and through more of an uncanny figure though makeup and posturing than an obviously lively and pretty woman in a baffling choice, is shaped into the true subject of the fight against Dracula, learning out of her fears of the pervading evil a precious expertise and executing out of her love for her weakened husband the actions that could save her environment, without much success, and destroy her nemesis, with more success – and then not.

The film does not end with Dracula’s real death and even less with any kind of happy ending: to the contrary it settles on an utterly upsetting and ironic conclusion. Far from being cured and saved, and grieving for his lost wife, Jonathan Harker rises more callous and resolute he has ever been, his teeth taking the shape of Dracula’s, his eyes having a disturbingly malicious glint, his voice betraying hostility and arrogance. As he rides madly his horse toward a strange horizon, in another epic vision of nature, he is definitely a hero but the new courier of terror, the descendant of Dracula, the vampire of a new era – Dracula may be dead but the evil he embodied is still ready to strike and to thrive, a radically pessimistic vision that may well be an echo to the fate of Germany in the decades that followed Murnau’s film.

The living are not the only ones to have been transformed by Herzog: so has been the undead. This Dracula is as wicked and bloodthirsty as could be expected, a scaring presence whose eagerness to invade and kill is brilliantly chronicled by a camera shooting with urgency and flair. But, shot in a peculiar cinematography, he does not always cause fear but instead intrigue: the mien, the gaze, even some words express a strange but haunting melancholy note. The monster has a romantic edge suggesting a tragic fate deeply felt as such, a yearning for ordinary love and death, a more complex and nuanced character than what cinema has so far depicted. Played by oddly drained but mesmerizing actor Klaus Kinski, reuniting with Herzog to provide a performance that is once again awesome but the polar opposite to what he delivered in “Aguirre, der Zorn Gottes – Aguirre, the Wrath of God”. This is not the least surprise in this new look at Murnau’s legacy (other images float in the mind even after the ending, like Lucy Harker’s walk though the plague-stricken town revealing people who, far from being intimidated by the disaster deliberately choose to party, a last pursuit of pleasure in the shadow of death, an unorthodox embrace of hedonism in a strict community buffeted by an incomprehensible horror, and one of the strangest image the story of Dracula could have suggested).