United States, 1961

Directed by Stanley Kramer

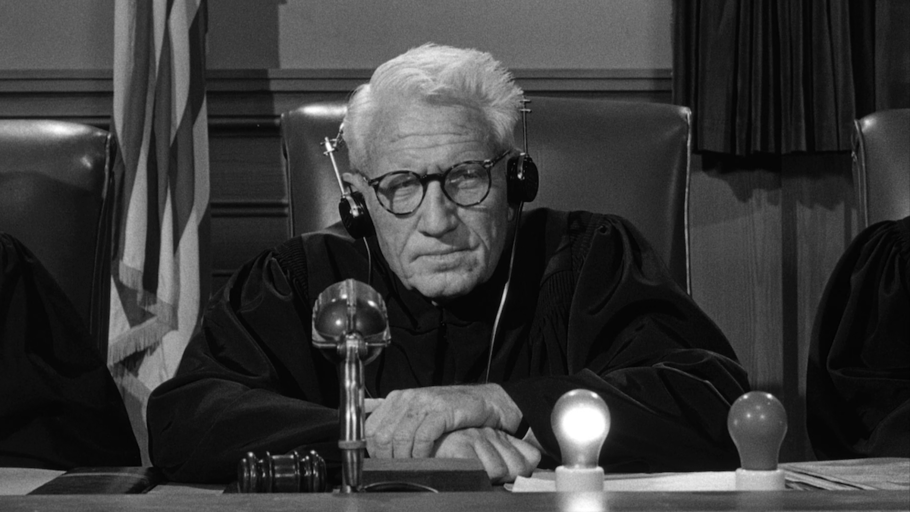

With Spencer Tracy (Judge Dan Haywood), Richard Widmark (Colonel Tad Lawson), Maximilian Schell (Hans Rolfe), Burt Lancaster (Ernst Janning), Marlene Dietrich (Mrs. Bertholt)

This is a fiction: the film does not reconstruct real events but the plot is based on the so-called Justice Trials that took place in 1947 within the wider frame of the Nuremberg Military Tribunals. The first trials of the system famously dealt with the surviving political leaders of the defunct Nazi regime but in their wake a series of other, lesser-known trials targeted various members of the bureaucracy and the elite of the Nazi Germany. In the case of the Justice Trials, four defendants were tried for holding responsibilities in the Nazi justice apparatus, in particular Franz Schlegelberger, a brilliant legal mind and former minister of the Third Reich.

The narrative begins with the arrival in Nuremberg of Dan Haywood, a retired American district judge who has been appointed to preside over the trial of four judges. It ends with his departure some ten months later, just after he delivers his verdict. Apart from a few scenes featuring the defendants in their jail or focusing on the military, the film alternatively shows the trial’s proceedings and the judge’s private life as he tries to mingle with the locals.

Both parts of Haywood’s German experience are dominated by a singular and strong personality, representing the old nobility that grudgingly worked with Adolf Hitler. If four men are in the docks, only one has a counsel; he is Ernest Janning, who was an authoritative legal expert, a supporter of the Weimar Republic and eventually a senior official in the Nazi Justice Ministry. He is aloof and quiet while his lawyer Hans Rolfe is pugnacious and loquacious. The quarrels about his case rapidly take center stage, shadowing the other defendants and intriguing Haywood. Meanwhile he gets more intimate with the landlady of the mansion he lives in, Mrs. Bertholt. She is the widow of an army general found guilty and executed after another Nuremberg trial. She strives to help her native town to get rebuilt and, increasingly, to explain Germany to Haywood. Both characters’ complex nature gives the film a precious sense of nuance, avoiding simplistic descriptions of a nation and its people.

Haywood comes across right away as a quiet American, proud to serve his country, but aware of the daunting difficulties of his brief. The trial proves to be hectic as Rolfe, in his distinctive cunning and passionate manner, puts on the defensive the prosecutor, Colonel Tad Lawson, whose zeal leads him to present flimsy evidence. Their fierce procedural clashes and their aggressive take on the witnesses weary the judges and make the whole business unwieldy – till Janning tells his lawyer off and gives a lucid, eloquent, and heartbreaking account of his career as it erred on the evil side.

This dramatic moment of sincerity, which did not happen in the real life (Schlegelberger was unrepentant), puts Haywood ever more in a bind. As he tells Mrs. Bertholt he ends up unable to know what to think. The question of personal responsibility within a system clearly bent on destroying lives lies at the heart of the trial and a film which offers an interesting twist on the typical trial movie as it is the very work performed by judges that is the subject of the proceedings. World politics add another burden to Haywood’s plight as the deepening confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union jeopardizes the safety of Berlin and prompts eager American political and military officials to plead for a quick end to the trials and lenient judgments; this poisonous climate politics forces on justice is deftly addressed by the film.

Haywood, rigorous and undaunted to a fault, would deliver a harsh judgment, dismaying a lot of people. In his final encounter with Rolfe, he praised the legal expertise of the young German lawyer and his logic, but explains that Rolfe’s logic is not so fair. He has tried to be fair all along and that was the point for him in those very peculiar circumstances. They are clearly articulated by director Stanley Kramer who shares the same passion for fairness as his conscientious lead character. As the camera shots one close-up after another, circles around faces and paces streets and places, he gives in a forceful style a most intimate look at characters who are trapped by both the justice system and the terrible weight of history – and doomed to feel overwhelmed or let down (Mrs. Bertholt’s being a heartbreaking instance played in almost magnetic and memorable terms). Every word matters and both intimate dialogues and the vivid scenes of cross-examinations sound remarkably relevant, accurate, and poignant.

There is an intelligence of the travails of justice that stands as remarkably honest and even moving in the never ending effort to give all the arguments the better attention. Three hours were needed, indeed, to achieve this powerful portrait of moral dilemma and political tragedy and they never felt too long thanks to a cast of incredibly dedicated actors playing well written roles with all the passion their talent could manage (for some, the then nascent 1960s decade was to be their careers’ twilight). The whole exercise may feel old-fashioned for some in the early 21st century, yet we should be grateful, at a time of highly partisan debates, accusations, and interpretations, on so many matters, including law, that such a film demonstrates cinema can deal with such a morally tough topic with talent.