India, 1964

Directed by Satyajit Ray

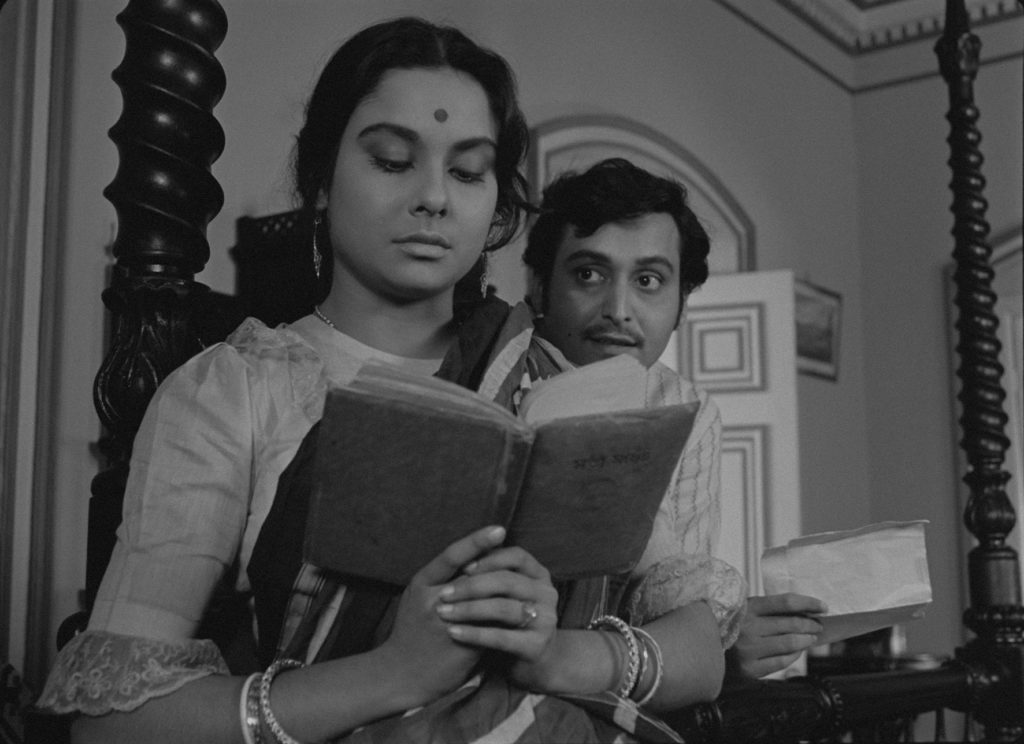

With Madhabi Mukherjee (Charulata), Shaileen Mukherjee (Bhupati), Soumitra Chatterjee (Amal), Shyamal Ghoshal (Umapada), Gitaly Roy (Mandakini)

A young woman is embroidering a handkerchief in her room. Then, pleased with her work, she starts walking around the big, lavish house where she lives, at one point looking for a book she could like in a bookcase and at another moment touching briefly the keys of a piano. She obviously belongs to a wealthy and educated household – and it is as obvious that her life is remarkably dull, although she gets easily entertained by observing the streets with her elegant binoculars. Hers is truly a quiet life: the shots of this delicate, behaviorist introduction to the titular character are remarkably silent (save for a brief remark to her old servant).

The problem underpinning Charulata’s boring and isolated life is disclosed out of the blue at the end of this exquisitely crafted prologue: a man appears, walks down a corridor, engrossed by his thoughts, and then comes back with a book in his hand. He has never cast a glance to the woman, who has observed him throughout, standing opposite to the camera.

This man, Bhupati, belongs to the indigenous upper class in the 1870s Bengal. He has chosen to take part in the political debates of the time (the fierce discussions about the British rule’s legitimacy and the need for Indians to rise up, that is, the development of a nationalist awareness and agenda) and founded an English-speaking newspaper highly critical of the Raj. To edit it is a challenging endeavor which harnesses his energy, attention, and money (moreover, the paper’s office and prints are settled in a wing of his Kolkata mansion), and ends up neglecting his wife Charulata without fully realizing it.

Things change for her when other family members come. On one side there is Umapada, Charulata’s brother, whose help has been requested by Bhupati to run the paper and who arrives with his wife Mandakini; on another side, Amal, a cousin of Bhupati’s, pays a visit after graduating from the university. So Charulata is no longer alone and her home, including the section devoted to the paper and the garden where she spends more and more time with Amal, is humming with activities.

Both men eventually prove to be dangerous for the couple’s stability and prosperity. Umapada’s case is dealt quickly, in a late development of the narrative: a first scene shows him talking in a suave, conspiratorial to a worried Mandakini, and then a second one records how he takes money from Bhupati’s safe; a later scene, one of the only two in the entire film that are not shot inside Bhupati’s house, makes plain what disaster actually happened as a business partner gives evidence that Umapada has stolen Bhupati, shockingly betraying his trust and hopelessly ruining his business.

The harrowing development turns out to be just the harbinger of the greater crisis that would assault Bhupati at the very end of the film, when he witnesses by chance and in secret a nervous breakdown of Charulata provoked by her reading again a letter Amal has written to them a few weeks after he left them. The sound of his feet running away betrays him and Charulata realizes she must now cope with a husband fully aware of the sentiments she and Amal have for each other – that other trouble the arrival of their relatives has brought to the tranquil life of Charulata and Bhupati.

Unlike Umapada’s dishonesty, these sentiments have not led to shocking acts, however. They have not taken the form of whispered avowals and romantic gestures. Words have played a role but they have carried other meanings and used another ground than intimacy. Charulata and Amal have learned to like each other and to feel a common harmony through a shared passion for literature.

Writing a story on the notebook Charulata gave Amal turns out to be the first step in their romance. A wonderful, highly dynamic and poetic cross-editing juxtaposes images of the pages being feverishly written by Amal and a stream of shots capturing Charulata’s mien and attitudes as she plays with a swing, daydreams, and casts a watchful glance on Amal or an inquisitive one around the place during a delightful afternoon in the garden: the hopelessly shiftless young man at long last dares being creative pleasing his mischievous cousin who dares dreaming to another life. Their fist quarrel comes when Amal decides to publish this story in a review even though he has promised to keep it private. That drives Charulata to become a writer on her own, and after another literary review accepted her text, she loudly and confusingly expresses her revenge, hitting Amal on his head with a copy of the review and flying off the handle before sobbing in his arms. The shot on Amal at this point shows how stunned he is, realizing something deeper may be at stake – and anyway, something quite important did happen: a woman managed to get her name published, to stand on the spotlight of a bustling intellectual and political scene, far away from the discreet, confined life of a conventional housewife.

After this dramatic event, their minds get more responsive to each other and Amal’s prankish attitudes and Charulata’s mercurial and excited ways hint at stronger feelings. She can exudes childish joy but is also quicker to show her worries about him, in particular when Bhupati tries to get the boy married. The common angst that surfaces when they realize something has happened to Bhupati, the day the man understands he has been cheated in his business points to how deep their bond now is.

In this scene, as it has been often the case in the film’s constantly artfully designed camerawork and cinematography, with a spectacular interplay of lights and shadows and the tension created by the positions of bodies or faces in the shot composition, this bond’s absolute reality is fully conveyed. And yet it remains somehow inarticulate: neither Charulata nor Amal dare to spell out clearly what they feel, or even cleverly suggest it, rather fumbling for words and hesitating to look at each other – out of respect for Bhupati, constrained by propriety and tradition, of course. Their deeper feelings have been in fact suggested all along through his customary frivolous ways, her surprisingly petulant outbursts, dreamy stares, listless attitudes, and a pair of embroidered slippers Charulata intends to offer him though they were made intended for her husband (the way these shoes are shot movingly emphasizes the changing fortunes of her heart).

Even the abrupt end of the affair is more a heartbreaking symbol than a dramatic, confrontational (and thus expected) incident. Amal is shot writing a letter explaining he must go, with the face, looks and gestures of the actor signaling utter sadness but then he is shot walking away silently in a corridor in the dark of the night, captured by a remarkable long shot: this is over with less than a whisper, and certainly not a bang. This is the fitting end of a romance that has been powerfully subdued; it does not bloom in usual narrative terms but rather in a gorgeously oblique way, it is really a triumph of the unspoken, even as emotions racked the characters’ faces – it may a mute affair but its impact is nonetheless deep and shattering.

The film lets this impact fully felt by taking Charulata’s viewpoint. From the first pictures onward, she is present in most scenes, often shot in dramatic lights or compositions (the camera relishes in moving swiftly or taking a bold, surprising angle), the camera intently focusing on her beautiful face, with a few POV shots letting the audience see the world through her cherished little pair of binoculars, in particular during that delicious afternoon in the garden, when she looks at Amal in a fresh way, but also pays a sad attention to a neighbor playing with a baby – a poignant reminder her married life is still childless, somehow unfulfilled.

“Charulata” is the detailed and elegant examination of a wonderful woman left alone in a corner of a magnificent house and at the fringe of a changing society (the scenes focusing on Bhupati capture the excitement among the Bengal elite about the possibility of changing India) but who becomes increasingly aware and proud of her sensibilities. Love and literature blend to help her assert her personality and her right to happiness and success – at the risk of breaking the nest she has conventionally built with Bhupati. “A broken nest” is actually the title of the short story written by Rabindranath Tagore that director Satyajit Ray is adapting here. He ends his film with a brief series of still images that underlines the harrowing situation Charulata and Bhupati must deal with. Time has stopped and fate is yet to take shape – but whether the wife and husband relation can be mended remains unclear; after all, despite her generosity, as she firmly extends her hand to her husband, Charulata is no longer the quiet wife who just embroiders things. She has found ways to be as independent and strong as her country reckons to become one day.