(West) Germany, 1973

Directed by Wim Wenders

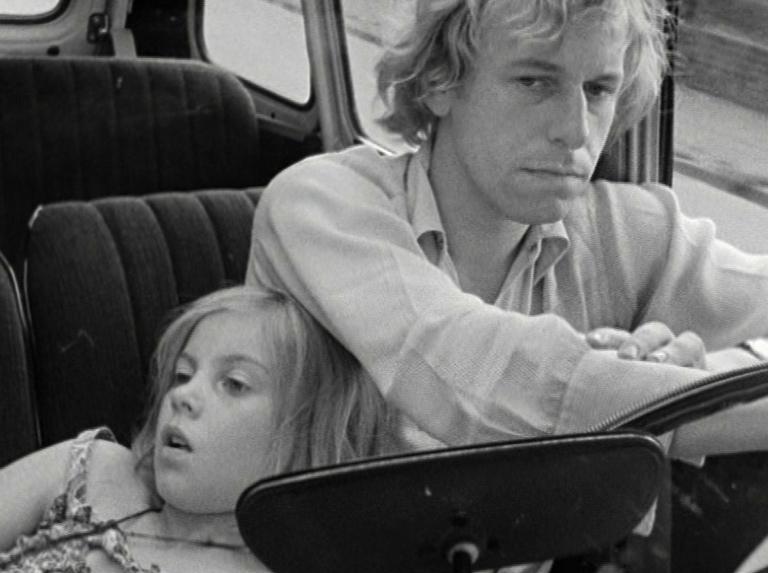

With Rüdiger Vogler (Philip Winter), Yella Rottländer (Alice)

Even if the title brings to mind the novel of Lewis Carroll this is not a tour in a parallel, fantastic world but in the urban places of the Western modernity while embracing an even wider scope: the film begins with the image of an airliner scudding through the sky, probably above America where the story begins, and ends with a spectacular tracking out shot moving away from a huge train speeding on the ground of a valley in Germany and capturing the wider, mountainous around it, panning then to the right to show the horizon.

The titular Alice does not take the center stage from the start – or even later. She travels with a companion she was not expecting, and neither was he. It was a matter of kindness at the start: Philip Winter needed to leave the United States to go back home, in Germany, because he lacked money and has a job to finish. In the New York offices of the Pan Am airlines he helped a woman buy tickets for her own return to Germany with her daughter, for she no longer got along with her husband. The three of them then spent the night at a hotel as their plane was only available the day after – and could by the way only carry them to Amsterdam because of strikes in the German airports. But when time came to move to the airport Philip was noticed the lady changed her mind and went back to her husband to smooth things over; so he was forced to board the plane with Alice. And it was just a beginning: Alice’s mother did not turn up in Amsterdam and did not sent a message. So Philip and Alice must stay together and keep traveling, this time to find the kid’s granny.

Those key developments in New York and Amsterdam separate two long sections which pertain to the road movie genre, endless trips on the road through varied and spectacular landscapes. Both these sections stand in sharp contrast – in the first the camera is often trained on the road seen through the windshield as if it was on a never-ending stretch leading to an elusive horizon; the trivial events of the trip highlight how Philip and his car are just lost elements inside a wide space and how it makes him increasingly uneasy; but in the second the camera is keenly focused on the two lead characters, examining the space between them as much as the urban but quiet surroundings, tracking their wanderings through Wuppertal and the Ruhr region with a far more relaxed point of view.

These differences tell the real narrative of the film, the slow transformation of Philip. If from the first image featuring her onwards Alice looks like as a clever child, quite outspoken and with loads of common sense and some tricks up her sleeve, Philip has always been cast as disgruntled and insecure – a man hiding below a deck on a desert beach to shoot pictures of the sea, barely talking to people but talking to himself, careless and awkward. If Alice can fare by herself and proves to be obstinate, Philip is far more skilled and definitely unsure of what he needs and what he thinks, which is fairly embarrassing as he is a writer and his writings are eagerly awaited by a publisher.

But the fact is that long road trips through the United States only yield boxes of Polaroid pictures and zero text: to him the experience has been completely alienating and he feels at a loss. He sums up his situation as being in trance to a New York friend who does give him a warm welcome at all, quite the contrary: she insists he is just unable to manage his life and by the way that he must get out of her apartment. This is a dejected man whose bursts of anger on the road have been puzzling and have certainly no relations with a kid’s whims. Yet these so distant persons would succeed in getting closer, to Philip’s benefit.

The obvious differences between the landscapes surrounding him nicely illustrate that long move by Philip from loneliness to companionship but what matters most is the dialogues and the behaviors, the building of a bond by words and gestures. It is telling Philip can at long last create a fresh story because he was asked to by Alice as she wanted to fall asleep – that was not easy: once she begged, he exploded, claiming he did not know any bedtime story; but then he retrieved his composure and the film got one of those stunning moments when Alice’s whims alter the dynamics, carrying the narrative to an even more tender, funnier grounds, away from the awkward situation of the beginning and further in the growing field of love that keep them together. When Alice flees the police station where Philip brought her because he sorely lacked money and was tired with the task of looking for the grandmother, he does not try to get in touch with the police but happily moves along with her – a bizarre attitude a policeman denounces at the end but the obvious hint that their relations have become too strong to be ripped off. And even in the train carrying them to that granny who looked life for so long as a mythical Holy Grail but who is real and has her daughter, the vanishing mother, at her side, they cannot stand apart.

Philip has discovered a kind of personality he clearly never thought could exist (at 31 and with no stable life he cannot seriously entertain the idea of family; anyway remarks he makes suggest the way he looks at his own relatives is not gentle) and whose energy has upset him. Alice, despite her grumblings and sarcasms, has also found a delightful companion perhaps better than a real father; but even she is a kid, she stands as the creator of this companion, quietly bringing to life traits that have never been evident earlier in the film and giving clues about what do to in a life – if only a brief period. At least Philip cannot say to be in a trance; he is a living part of the wider world, attached to it, no longer lost but aware.

“Alice in den Städten – Alice in the Cities” is not just about personal adjustment. It does convey images and sentiments about a cultural adjustment regarding Philip as an intellectual striving to feel and as a mirror to the director. Wim Wenders is then a young, promising director typical of a European arthouse culture – but here he decides to use a typical genre of the American cinema. The first part is sprinkled with references on the American culture, from television series to extracts of old movies to paperback books, like the many nods to the images and words from America a lover of American cinema could obviously make, and is shot with as much care for compelling details and genuine atmosphere as it could be expected on that side of the Atlantic. But the topic is actually the failure of Philip to connect to the reality. To him the experience is dull and even dumb: he cannot delineate preconceived images from his surroundings – in fact he claims they are the same – and he would go as far as destroying a television set in a motel room before moving back to New York in order to flee. America is a dream turned disappointment.

But Germany is not enough to him: driving desultorily through the native land in search of the grandmother should offer the comfort of the well-known and cherished things and may still play a part in his evolving relation with Alice. Yet once he left her at the police station, he goes to a concert given by Chuck Berry and the show itself is featured in a rather long sequence. And the last text he is seen reading, with a close-up on it that has never been used before on texts in the film, is the obituary of John Ford published by the daily Süddeutsche Zeitung – remarkably titled “A Lost World”. Viewed from afar and through cultural creations America still beckons to the mind, tough also on nostalgic terms; but on the ground it was so different as to raise the question of how seriously intellect can reconcile feelings and perceptions. Alice, by the way, seems unconcerned by such a trouble: she may too young and certainly too spontaneous, confident, open to make friends (that delightful way to connect and play with another kid on the back of a bus bound to Wuppertal) for that.

On cinematic terms, that is as far as Wenders’ skills are concerned, the film is still a remarkable effort to harness the possibilities contained within the genre. It yields convincing scenes both in the first part and in the second but the most important, moving and delicate events take place in the native land. If America provides inspiration, Germany defines the sense; in this kind of Bildungsroman turned upside down (with the youngest shaping the eldest and the knowledge becoming akin to a psychological blossoming, not so much a morality tale or a conquest of wisdom) image from a distant but still close modernity offers a fresh way to examine alienation and awakening, loneliness and companionship and the poignant move from one state to the other. Wenders can be as satisfied with the trip as Philip is.