Japan, 1985

Directed by Oshii Mamoru

(Animated movie)

In a film where words are sparse, the first to be uttered, which swiftly give way to a long string of voiceless scenes (save for the choir that is part of a gracefully mournful soundtrack redolent both of the Middle Ages and the most contemporary music) point at what may be the most essential riddle of a most enigmatic and puzzling story. A young girl’ voice asks someone who he is. This someone quickly looks like the young and lonely soldier standing at the beginning on the ground of a futuristic landscape staring at a strange vessel rising in the sky, shaped like a human eye, whose insides are festooned with countless arches that seem more flourishes than supports, an odd architectural fantasy comprising rows of human-like sculptures, but without any weapons or noticeable engines, a stunning and giant object that conjures up obviously sci-fi images of spaceships and yet looks quite apart from the genre visual tropes.

This strange vessel would rises back from the sea in the final shots of this short feature (the runtime is barely more than 70 minutes), once again observed by the soldier standing this time on a much familiar and verdant ground, the rows of sculptures now completed by a statue of the little girl the soldier met and accompanied and looked after only to break what she protected and abandon her – unless it is the girl, previous scenes pictured as dying in fall, who has become herself a statue after embracing her reflection in the river running at the bottom of the deep ravine she fatally failed to jump over. Can it then be the soldier’s mission was indeed to find her and to alter the course of her desperate wanderings inside a dreary and dark city without any real human or animal, only shadows of soldier-like fishermen and giant fishes, the former darting and bolting to seize the latter which hover above the empty and dirty buildings?

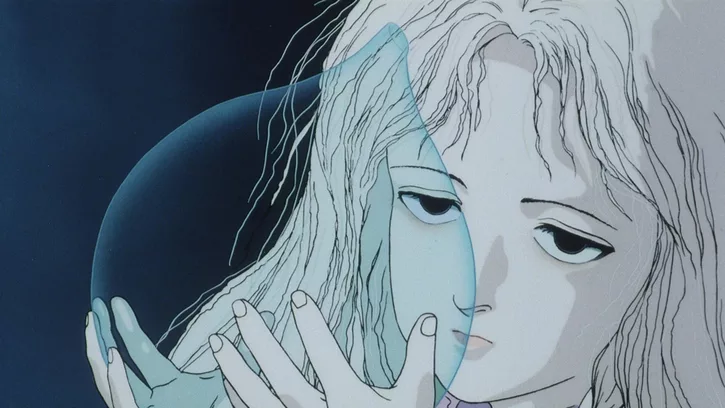

To resolve the riddle of this sad, quiet, soft-spoken, resolute, nice-looking too, soldier, especially with such an hypothesis is to make sense of a story giving away next to nothing in terms of background and meaning. Even when they ask questions and exchange tales, the two characters end up adding more enigma to the baffling and frightening situation they are. What can be made from stories about birds and trees even though the most striking feature of the sheepish, pale, wretched waif is the seemingly very precious and very large egg she constantly holds concealed under her reddish rags – but also warmed, as she explains at one point she hopes it would break and give birth to a bird? What can be made from the long (by the quiet standards of this film) yarn the soldier spin about a disaster sounding very much like the Noah’s story of the Old Testament, even if no source is acknowledged and no further explanation delivered, though that story could account conveniently for the city’s emptiness and damages?

But the very peculiarities of this city, a stunning, slightly distressing and really fascinating, mix between the European buildings of the 19th century, perhaps 18th century too (the Paris of the boulevards can spring to mind), the Baroque style, the Gothic features of the Middle Ages and also the Gothic flourishes and singular atmosphere of the English and American literature and visual arts, precisely because they are so arresting and prominent, can also suggest the whole point is not to tell a story, and certainly not within a rationalized frame, but to let the audience feel.

The film could be a mere, specifically apocalyptic, vision, a bad dream with its own weird logic dealing with fears about civilizations’ existence and notions of survival and revival. Those strange tanks, cumbersome reddish machines throbbing also like animals, straight from a Japanese sci-fi anime, rumbling through the avenues, can be the convenient, recognizable sign indicating ominously an Armageddon which is soon to come or has perhaps already come while the egg raises self-obviously the issue of birth and death, possibilities of renewal, redemption even, or more basically survival or miraculous continuity. The plangent soundtrack and the somber scenes by night showcasing those strange shadows or just a depressing bad weather or some distressful ruined places, which are arguably as much a large part of the film as any interaction between the characters, if not more in terms of runtime, hog the attention and capture the attention constantly and the audience can rightly feel as mired in this bleakness as the waif and the soldier.

Director Oshii Mamoru, by then not even ten years into a directing career that started with television series, claimed that he himself had no idea of what he wanted to articulate and to narrate when he was shooting this very personal and unusual anime, his third feature, but was simply carried away by images and sentiments, letting them draw this terrible world, those mournful creatures, those riddles that are as many queasy evocations of deeper questioning and anxiety. This is what can be readily experienced and probably the only thing to get from the film – and this is not diminishing its aesthetic and intellectual worth.

Here is an anime, especially an anime pertaining to the science fiction and horror realms, that does not appeal to an imagination shaped by what is expected, feared, hoped, speculated from the scientific and technological knowledge, that does not cling to simple narratives of good and evil, brave natives and callous aliens, or dazzling heroism and spectacular dangers. This is an anime that builds on the dizzying, puzzling, troubling, lingering, fascinating traces that a bad dream can leave, the discombobulating and yet compelling logic of a dozing mind, a sense of the future owning everything to deep-seated fears as well as long-established cultural legacies. It must be watched the eyes wide open and the mind even more opened and free, without the reward of a narrative well made but with the pleasure of a visual experience.

The audience can honestly fail to be seduced all the time by the animation or that white-haired waif whose looks can be a bit too flat and sullen or this purposefully enigmatic soldier whose looks can be a bit too stiff, and even less by the absence of clear narrative arcs. But once again, it is not the kind of slick and snazzy sci-fi, or any other kind by the way, anime that targets box-office success and as a consequence is produced within conventional parameters. If there is a lot of attention and hard labor behind “Tenshi no tomago – Angel’s Egg”, it is because it is not sticking to banal rules but expresses personal emotion, view, and talent, and asks to be watched with fresh eyes and in an open-minded mood. This is a pure poetic gesture, no less, putting it firmly in the realm of the most ambitious and astonishing creative productions in cinema history.