United States, 1951

Directed by Albert Lewin

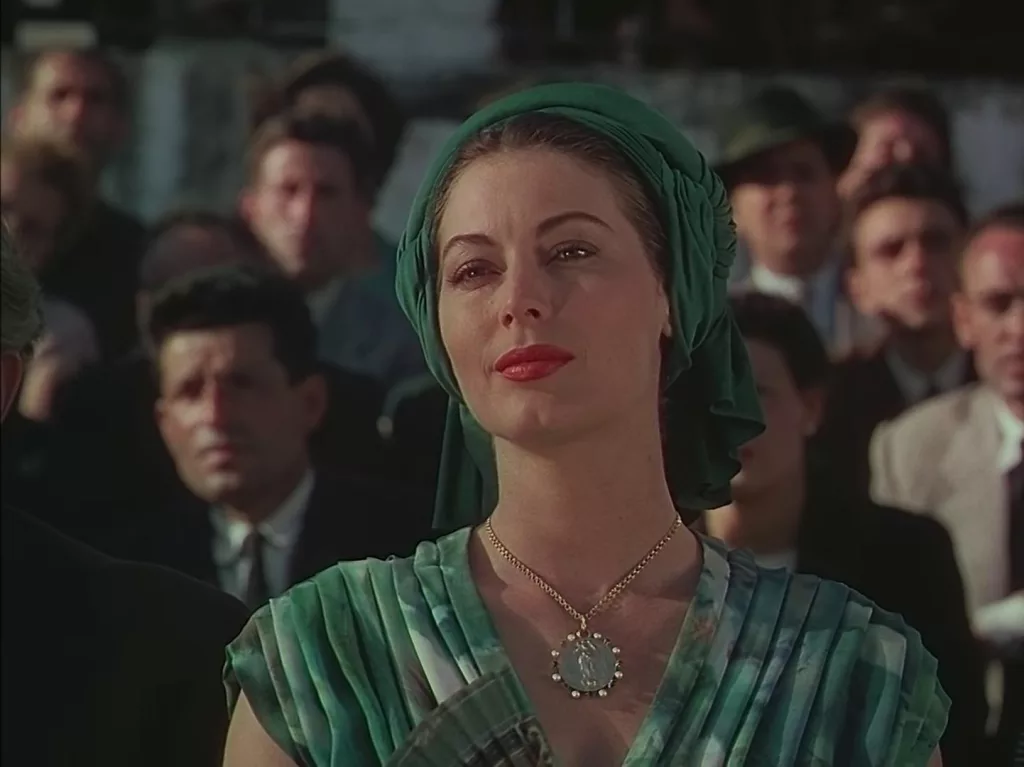

With Ava Gardner (Pandora Reynolds), James Mason (Hendrick van der Zee), Harold Warrender (Geoffrey Fielding), Nigel Patrick (Stephen Cameron), Mario Cabré (Juan Montalvo), Marius Goring (Reggie Demarest)

The title is a bold association: on the one hand Greek mythology and on the other a famous occult tale, which the film tinkers with. As the Encyclopedia Britannica explains, “the Flying Dutchman, in European maritime legend is a specter ship doomed to sail forever; its appearance to seamen is believed to signal imminent disaster. In the most common version, the captain, Vanderdecken, gambles his salvation on a rash pledge to round the Cape of Good Hope during a storm and so is condemned to that course for eternity”. It also notes that “another legend depicts a Captain Falkenberg sailing forever through the North Sea, playing at dice for his soul with the devil”.

The point is, the Flying Dutchman is a ship, not a man, and literature has deferred to this idea, whether it is the poem “Rime of the Ancient Mariner” by Samuel Taylor Coleridge or the poem “Rokeby” by Walter Scott. However, Heinrich Heine had other ideas about the legend, explaining the misfortune of the captain by a tragic love story. Heine’s text became the basis of the opera “Der fliegende Holländer” by Richard Wagner, and this is what director Albert Lewin recycles in his fourth feature, while confusing deliberately the captain and the ship, and moreover giving a new name to the man, Hendrick van der Zee.

Pandora is also a new person: no longer the beloved companion of the Greek gods, Pandora Reynolds is a torch singer without a dangerous box but instead with a mesmerizing power of seduction, a beautiful young American who drives men mad but seems to be unwilling to take anything seriously, not even life as she claims, and yet looks for an overwhelming sentiment that would fully satisfy her.

Reusing endlessly and playfully cultural references looks sometimes like the film’s only purpose, from the occasional transformation of the small Spanish fishing village where the story takes place in 1930 into an eerie field of Grecian statues and ruins (even if the confidante of Pandora Reynolds and Hendrick van der Zee and the narrator of their story, Geoffrey Fielding, explains he chose to settle in this place because it was known to Phoenicians, seemingly his specialty as an archaeologist), to the paintings made by the Flying Dutchman which look like tributes to Surrealism (indeed Surrealist artist Man Ray contributed to the film), to the supposedly enlightening reference to the “Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam”, the translation by Edward FitzGerald from Persian to English of quatrains attributed to the 11th century polymath and poet.

The film also juggles various elements of modernity (as it could look like in the 1930s) and traditions associated with Spain. The camera avidly shoots fairly stereotypical folk elements, from a flamenco dance as early as the second sequence (which starts the long remembrance that Geoffrey Fielding’s narrative is) to a spectacular corrida, courtesy of the toreador Pandora Reynolds refused to marry, Juan Montalvo – but the village’s beach would be the track on which a sports car, built and driven by Pandora Reynolds’ ardent suitor, Stephen Cameron, attempts to break a world record of speed, a terrific episode illustrating the appeal of sport, stunt, and mechanics defining the 20th century. The film blends also genres: a ghost story stokes a romance while a flashback turns the chronicle into a period piece set in the 17th century Holland.

“Pandora and the Flying Dutchman” does not shy from dropping big hints and highly significant details, advertising highbrow culture and self-reference, in a hopelessly conspicuous manner: the name of the lead male character, Zee, is conveniently the Dutch for sea, while the village is named Esperanza; as Geoffrey Fielding remembers the events leading to tragedy he is busy working on pieces of an old shattered vase, slowly building it back to shape as he speaks, and of course, when he is finished, the vase stands nicely reconstructed, while the telescope in his studio at the top of a house perched on a rocky hill would enable him to watch many things, and actually is the optical tool which reveals to him the tragedy, a view from high angle matching the camera’s trend to shoot characters and events from a high angle.

There is two possibilities: either the audience is willing to get impressed and let themselves carried away by the arguably sophisticated and painstaking tapestry those borrowings and tricks weave, or they can get a bit tired by the endless artsy, smart, self-conscious collection of visuals. It is hard to deny the imaginative and talented boldness of such a mixing of ideas and images but it goes easily overboard and beauty becomes a borderline case: culture threatens to be cant and craft threatens to be camp.

But this is not erudition that really shapes the plot, which is summed up by a quote the characters like to say and sounds authentic, although they do not know the source – in fact it sounds like a clever invention of the director. The phrase, “The measure of love is what one is willing to give up for it”, gives away early what is at stake: what could spur wonderful and whimsical Pandora Reynolds into making the greatest, that is the most sincere and deliberate, sacrifice proving she is truly able to love? She can drive a man to despair: that famous flamenco dance ends with writer Reggie Demarest, who has become a drunkard as Pandora Reynolds keeps refusing to marry him, killing himself. She can force him to make an absurd action – Stephen Cameron pushing his beloved sports car off a cliff – or inspire him to carry out a grim one – Juan Montalvo trying to murder Hendrick van der Zee. But if she demands a lot and if men are ready to do anything for her sake, it is not clear that she is willing to make any effort, change, or sacrifice, that she is even genuinely feeling any sentiment – the niece of Geoffrey Fielding is quick to claim she is insensitive and selfish.

This is precisely what the encounter with the Flying Dutchman would challenge. The wild and earthly female character is right away rapt by the mere presence of the stranger, and of his strange boat: high angle shots readily testify of the uncanny attraction she feels for the ship bobbing in the water by night. And the film would relate how she first she cheekily strikes a bond with the dour and distant seaman and then gets obsessed with him, sensing a mystery that overwhelms her day after day. When she learns about his real identity, she is not shocked or appalled, even less disturbed: she is more eager than ever to love him, and thus to set him free from his curse. Her life would redeem his past sin, and death would be a grace for both, even as their dead bodies would horrify – the first scene of the film shows how cheerful fishermen find the lovers’ dead bodies in their nets and bring them to the beach, an event viewed from the telescope of Geoffrey Fielding and thus the starting point of his long flashback-like narrative. A ghost has at long last led Pandora Reynolds to be a heartbreaking, truly romantic character, not just a simile of femme fatale.

And cinema allows the actress to become an icon on her own right, worthy of the sculptures, paintings, and rimes scattered around her. The film is simply a vibrant, gorgeously shot, vehicle for Ava Gardner. From frankly risqué shots at sea to the final embrace of her partner James Mason, her carefully heightened beauty stands at the center stage firmly and relentlessly. Actually, shots are sometimes a bit clumsy, with flawed back projections and stilted performances, but can also be, as the camera is focused on Gardner’s mesmerizing stares, masterworks celebrating the shine of a star, the flame of a romantic heroine brought to life, more or less compellingly, by legends and signs.