Japan, 1997

Directed by Kon Satoshi

(Animated movie)

A high-angle shot follows a trio of youngsters waiting for a concert by CHAM, their favorite Japanese pop group, to begin. After watching a performance by actors playing the heroes of a television series, they talk about the news that this could be the last gig of the all-female band, since the lead singer, Mima, is poised to start a career as an actress. Meanwhile, the camera in a fluid, continuous, roving movement captures the people going to the concert, including some louts. Cutaway shots focus on the band members getting ready for the show, including a highly nervous Mima. But other shots show her quietly doing her errands. The montage increasingly switches from the show to Mima’s household chores and back until it becomes clear that the latter takes place in the present time while the former was actually a long flashback (however, the viewpoint belonged to strangers). Once the narration’s time frame is clearly settled, anchored by Mima’s life, the titles begin, at last, to roll on.

The clever and confusing opening sequence gives away the narration’s radical and riveting nature. The images are not always what they look like prima facie, the montage compelling the audience to reassess carefully the meaning of the events. The borders between real facts and unreal visions get easily blurred and nothing can be taken for granted.

This visual choice perfectly suits the plot. The innocent chronicle of the transformation of a charming pop singer into a confident actress swiftly becomes more unnerving when Mima realizes a website devoted to her person publishes comments that depict precisely not only her more mundane actions but also some of her anxious feelings. Slowly she wonders how to feel about this strange double and her own life. Her story takes a decidedly more tragic and dreadful turn when people involved in her job get killed in grisly circumstances while she sees oftener and oftener her own person attired in the trademark CHAM scene costume and teasing her. Is she becoming insane? Is she still herself or isn’t it that the real Mima has now taken shelter on the Internet, as the website claims? Well, there is room for doubt, till the responsible for the manipulations and murders tears off the mask (quite literally).

Mima’s trouble and the audience’s doubt are bolstered by her work’s demands. She got a small part in a television program, a crime series whose heroes are a police detective and a psychiatrist working together. Under the pressure from one of Mima’s managers, Tadokoro, and with the approval of the network, the screenwriter widens her role; it becomes a part about a young woman suffering from a deep personality disorder and who is indeed the serial killer the series’ heroes are chasing. The fiction featuring Mima the actress increasingly feels like a distressing echo of the fiction centered on Mima the character, who struggles to cope with her new career. The demands the media system has for this new television star are clearly not the same as it used to be for the pop artist. Mima must accept to produce an image of her person that is anything but childish and prudish. The pictures of her naked body and of her playacting of a rape are harsh trials for her but also decisive steps – and shocking developments for her other manager, Rumi, and a fan of her past pop activities, a strikingly ugly young man who seems to be behind the manipulations and the murders that threaten Mima’s sense of identity and safety – but here again, it proves not to be that simple.

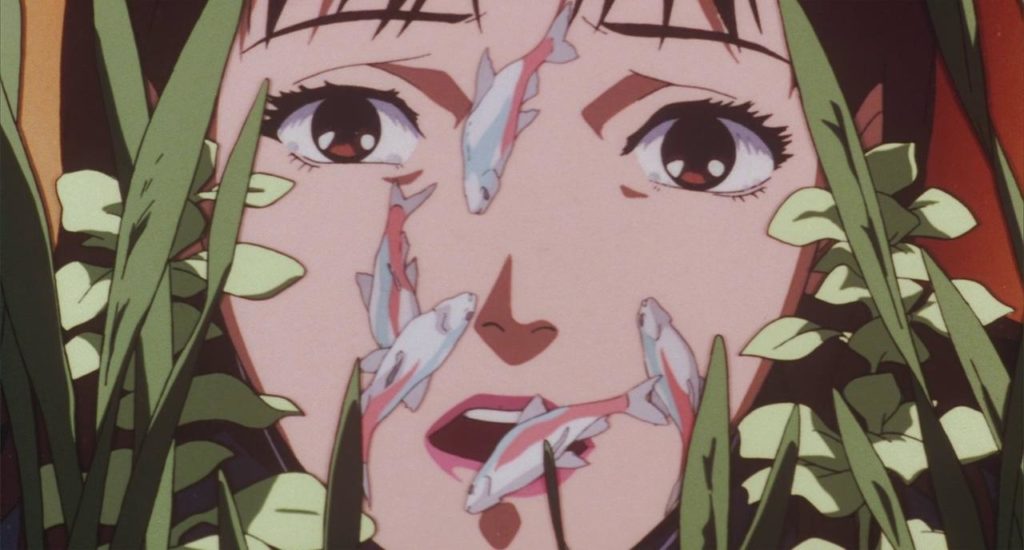

“Perfect Blue” goes farther and farther in representing the loss of certainty of the young artist and her growing fear that she has dived into an uncanny and nightmarish world; even basic facts and the passing of time increasingly elude her; once it was not sure whether the fish in her aquarium were dead or alive but at the end, in a stunning climax, three different scenes end with her waking up on her bed, making hard to understand what the actual events were. This ping-pong game between the images streaming from Mima’s mind and from her actual environment and between all those images and the twists and turns of the plot are a virtuoso’s work that is successfully creating a nerve-racking and oppressive experience for the audience.

Nine years earlier, Takahata Isao proved with “Hotaru no haka – Grave of Fireflies” that an anime was not doomed to deal about kids or teenagers’ stories and that the technique could smartly tell more serious and tragic stories. Kon Satoshi’s film feels like another landmark; anime can not only narrate a dazzling and puzzling thriller but also spur serious thinking. The masterful settings and characters design bolsters and enhances an ambitious plot while the entire film challenges the very nature of an image. Kon’s virtuosity is not a wanton performance intent on impressing the audience; it effectively questions how the perceptions on a celebrity are carefully built and how both the person and the audience adjust, or try to, to the created image.

The film explores the management of Mima’s identity and the troubles it provokes, in particular the convenient sexualization of her body, either as an infantile singer or as an arousing actress (the film makes plain stardom depends on eroticism), and the demands of virtual reality (this is one of the first film to grapple with the impact of Internet, back then a nascent popular phenomenon). This offers an interesting and unflattering examination of the business of Japanese popular culture; but it is first and foremost a stunning portrait of an innocent lady whose ambitions turn her into a borderline case.